Sunday, October 16, 2016

By Pat Thornton …

When domestic propane production began to increase in 2008, the United States started to rapidly become a net exporter of propane. As the capacity to export propane rose, we began to see exports reach new highs. By April of 2014, exports were going at a rate of 414,000 barrels per day and were up to 636,000 barrels per day by April 2015. The U.S. exported 886,000 barrels per day in February 2016, a new high that is more than eight times the export volume five years earlier, according to the Energy Information Administration (EIA). As 2016 has progressed, EIA has reported exports closer to 600,000 barrels per day through much of the spring and summer and more recently 424,000 barrels per day in September as the spread between U.S. prices and Middle East sources has increased. With the capacity to ship propane reaching new heights every year, it is uncertain if the world will continue to have an appetite for all the propane we can move.

Propane had fallen as low as 29.25 cents per gallon in Mont Belvieu in mid-January but rebounded by more than 80% to the 53-cent-per-gallon level by late May and remains just slightly under 53 cents per gallon in late September. The capacity to ship propane out of the U.S. continues to increase. Among other improvements to capacity, a major pipeline to be completed in 2017 will allow much larger volumes of Appalachian propane to ship from the East Coast.

Enterprise Products Partners has invested billions of dollars over the past 10 years to be well positioned to take advantage of the higher amounts foreign markets are willing to pay for propane and butane from the U.S. “Once we recognized that this country was going to produce more than it could consume, it became obvious to us that you need to be positioned to export,” said Jim Teague, chief executive of Enterprise Products Partners. A one-time two-truck shop founded by energy entrepreneur Dan Duncan, Enterprise has evolved into a global transporter of oil and gas.

With the shale boom that began in 2008, production of oil and gas were surging and two products that are pulled from the two raw fuels are propane and butane. Enterprise realized demand for propane and butane would likely not increase dramatically in the U.S. but saw that petrochemical plants in Asia were developing a strong appetite for propane and butane. Meanwhile, drillers in the U.S. were literally paying customers to take the fuel away. Enterprise decided it would link the U.S. excess propane and butane to the new demand in Asia—and elsewhere.

By 2013, Enterprise owned nearly 75% of U.S. loading capacity. In 2014 Enterprise and Oiltanking Holdings Americas signed a 50-year contract for Enterprise to be able to use more ship loading and dock space, but Enterprise wanted more than a partnership. By early 2015, Enterprise paid about $5.8 billion for 12 docks on the Houston Ship Channel and another 24 million barrels of storage for oil and refined products.

Others are expanding exporting capacity as well. With Occidental adding 75,000 barrels per day of capacity at its Corpus Christi, Texas, facility recently, and Phillips 66 scheduled to open a 145,000-barrel-per-day terminal at Freeport, Texas later in 2016, there will be even more capacity to ship well beyond the investment of Enterprise. All of this, combined with new ship construction and the expansion of the Panama Canal, makes it possible to further facilitate the flow of U.S. propane to international markets.

Enterprise is also a pioneer in the exporting of American ethane, a fuel that is a key ingredient in plastics manufacturing. Enterprise Products is ramping up usage of what is soon to be world’s largest ethane export facility at Morgan’s Point on the Houston Ship Channel, with two trains and two docks capable of loading about 200,000 barrels per day onto ships. This is significant to propane since there will be that much less ethane here to displace propane as a feedstock for making plastics, even as propane itself is also increasingly exported to foreign markets.

The vision of Enterprise that there would be Asian demand to be met has played out as expected. Asia is now the largest regional destination for U.S. propane with nearly 220,000 barrels per day shipped, slightly more than one-third of total U.S. propane exports in 2015. Transporting large quantities of propane over long distances requires specifically designed refrigerated ships. The largest, most economical class of these ships is the very large gas carrier (VLGC). Until recently only a limited number of VLGC’s with more upright hull designs were able to pass through the Panama Canal lock dimensions, but that all changed with the Panama Canal expansion inaugurated on June 26.

Panama celebrated the first vessel to transit through the 102-year-old Panama Canal on June 26 after a $5.25-billion expansion to allow the canal to accommodate large VLGC’s and other larger vessels. Panama hopes for a trade boost to allow it to be the “Center of the Americas.” With 35 to 40 ships expected to pass through every day, 24 hours a day, seven days a week, Panama hopes to be viewed as the logistic center of the Americas. With 166 reservations already on June 26 as the first larger ship transited, 17 were for liquefied petroleum gas. Panama is excited that the U.S. has become a net exporter of oil and related products to the rest of the world. Previously, size limitations of vessels caused larger ships to either travel all the way around the southern tip of South America or load from smaller vessels after they passed through the canal. This created bottlenecks and challenges as growing demand for propane from the United States continued to increase. Now, with the expansion complete, a trip to Eastern Asia for a larger ship went from 41 days to 25 days! Further, the production of more and more VLGC’s is lowering freight rates due to more competition, and the newest ships are also 17% more fuel-efficient.

The ship-to-ship transfers, where propane is transferred from larger ships to smaller ships to transit the canal, are no longer necessary. The process of multiple product transfers, or one transfer and then propane moving on to Asia on a smaller ship, is over. Not only is propane exporting more cost-effective, the actual sources and destinations are becoming more transparent. With all of the ship transfers that have been taking place at the Panama Canal, EIA has had to decipher confusing information, indicating for example more product shipments to countries such as China and Japan from Panama, a country that does not produce propane. Clearly these shipments were the result of a product transfer from another source, often the U.S. With the end of all the product transfers, we now have much more accurate data from EIA about U.S. propane moving to Asia.

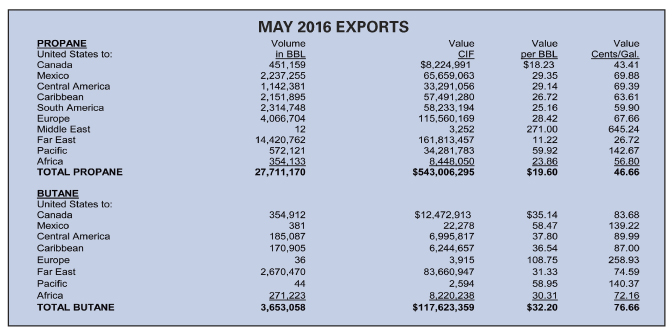

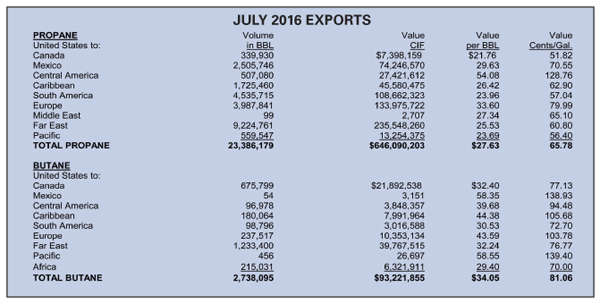

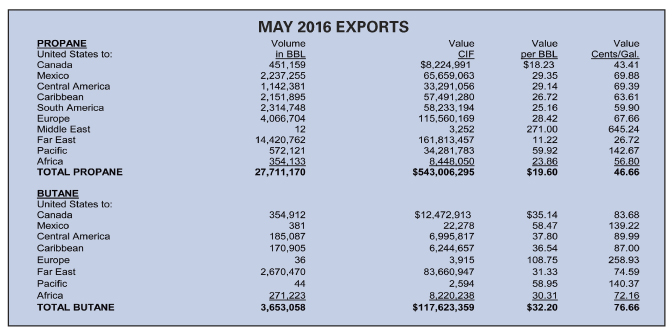

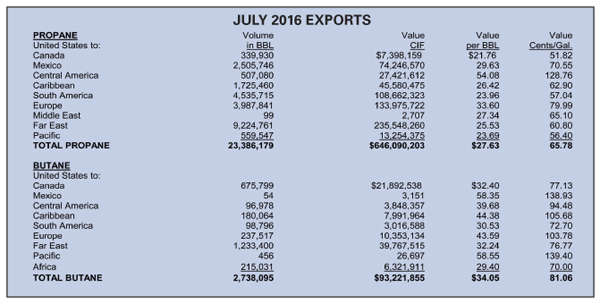

According to data from JBC Energy, propane exports to Asia this year were once close to a record 300,000 barrels per day. Meanwhile, let’s not forget propane exports to Mexico, the Caribbean, and South America doubled between 2010 and 2013, from 88,000 to 198,000 barrels per day. And exports to Europe have increased from 25,000 barrels per day in 2012 to more than 100,000 barrels per day currently. As mentioned earlier, the first quarter of 2016 showed propane moving to all export destinations at 886,000 barrels per day!

Asia is now the largest regional destination for U.S. propane with nearly 220,000 barrels per day, slightly more than one-third of total U.S. propane exports in 2015. Chinese propane dehydrogenation (PDH) plants have contracted 61 million barrels from Enterprise and Targa Resources from third-party traders, in contracts ranging from one to six years. Japan’s largest LPG supplier, Astomos, has contracted 5.9 million barrels from Targa over three years from late 2017, and its purchases 2014 to 2021 are 42 million barrels, mostly from Enterprise.

The completion of the Panama Canal expansion came as Middle East sources were becoming much cheaper than in the past and represented a turning point where Asian companies will be deciding whether they want to try to shift to shorter contract periods. While economics are a key factor, some have pointed out that U.S. supply offers more security than Middle East and Asian sources. The opening of the Panama Canal to larger ships, which cuts journeys almost in half in many cases, combined with lower freight rates as a glut of new vessels come online, will make U.S. propane more attractive. At one time there was an assumption that U.S.-sourced propane would always be cheaper, but that has changed.

There is no doubt shipping capacity from the U.S. has expanded greatly in the past five years as exports were pegged at 884,000 barrels per day in the first quarter of 2016, nearly eight times the rate of exports in 2011. Asian buyers may very likely try to cut their contract periods to six months to a year as lower prices for naphtha (with crude prices lower) and propylene have caused some to be locked into propane when there are better opportunities. Again, the original thought was that U.S. propane would always be oversupplied and cheap.

Recently there have been a greater number of cancellations of shipments from the U.S. due to the lower prices in the Middle East. In many cases, cancellation fees have been paid, since it was still economical to do so and take product from other sources. For now, the economics don’t favor a lot of shipments to Asia in the next couple of months and exports are pegged at 424,000 barrels per day in late September. However, this can once again dramatically change. With the export capacity in place, we must keep in mind just how much can go offshore, very quickly, once again. By the high demand months this winter in the U.S., world demand could be again setting new highs for exports.

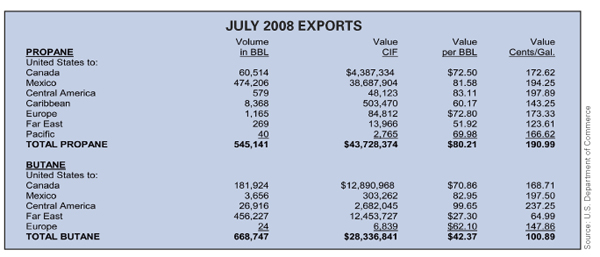

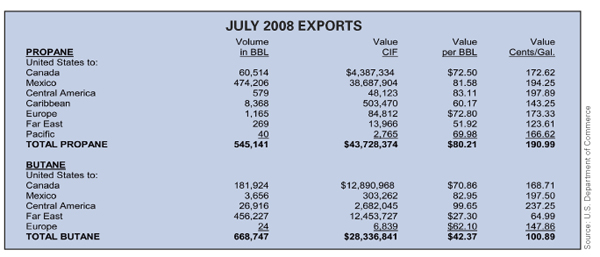

As we approach winter 2016-2017, U.S. retailers must understand how much prices in the U.S. can be dramatically affected by exports, or lack of exports. This isn’t 2008, when our capacity to export was limited to about 130,000 barrels per day. After a brutal January and February in 2014, many new rail terminals have been added in the U.S. to help meet domestic supply requirements, but we have not had cold enough weather since then to really test the infrastructure.

Unless we have a lot of rain in early fall, it is doubtful crop drying demand will be above average this season. La Niña conditions could bring about colder-than-normal temperatures, more likely in the second half of the winter season. This, along with exports ramping back up, could test our system and push prices up.

Many wild cards remain as we seek to figure out the direction of propane prices, and exports have become the wildest of the wild cards. Just like the question of whether world supply of crude oil will outstrip demand, there is the question of whether world supply of propane will outstrip demand. On the crude oil side, OPEC and other large producers hold the keys. As of late September, the organization has been more focused on expanding its own market shares and not agreed to cut production. If OPEC has accomplished anything, it has been undercutting crude oil production in countries such as the U.S. The collateral damage to propane has been the lower cost of naphtha and gasoline that it competes with. Most experts, including many world banks and EIA, expect world crude supply and demand to come back into balance in the coming year. Considering this and all the wild cards, we feel there is limited downside for winter 2016-2017. This is a good time to position propane not only for the coming season, but a portion for the next couple of winters as well.

Pat Thornton has been with Mission, Kan.-based Propane Resources since 1996, where he assists retail customers with hedging plans and provides risk-management and supply-planning services. He serves on the Missouri Propane Education and Research Council.

When domestic propane production began to increase in 2008, the United States started to rapidly become a net exporter of propane. As the capacity to export propane rose, we began to see exports reach new highs. By April of 2014, exports were going at a rate of 414,000 barrels per day and were up to 636,000 barrels per day by April 2015. The U.S. exported 886,000 barrels per day in February 2016, a new high that is more than eight times the export volume five years earlier, according to the Energy Information Administration (EIA). As 2016 has progressed, EIA has reported exports closer to 600,000 barrels per day through much of the spring and summer and more recently 424,000 barrels per day in September as the spread between U.S. prices and Middle East sources has increased. With the capacity to ship propane reaching new heights every year, it is uncertain if the world will continue to have an appetite for all the propane we can move.

Propane had fallen as low as 29.25 cents per gallon in Mont Belvieu in mid-January but rebounded by more than 80% to the 53-cent-per-gallon level by late May and remains just slightly under 53 cents per gallon in late September. The capacity to ship propane out of the U.S. continues to increase. Among other improvements to capacity, a major pipeline to be completed in 2017 will allow much larger volumes of Appalachian propane to ship from the East Coast.

Enterprise Products Partners has invested billions of dollars over the past 10 years to be well positioned to take advantage of the higher amounts foreign markets are willing to pay for propane and butane from the U.S. “Once we recognized that this country was going to produce more than it could consume, it became obvious to us that you need to be positioned to export,” said Jim Teague, chief executive of Enterprise Products Partners. A one-time two-truck shop founded by energy entrepreneur Dan Duncan, Enterprise has evolved into a global transporter of oil and gas.

With the shale boom that began in 2008, production of oil and gas were surging and two products that are pulled from the two raw fuels are propane and butane. Enterprise realized demand for propane and butane would likely not increase dramatically in the U.S. but saw that petrochemical plants in Asia were developing a strong appetite for propane and butane. Meanwhile, drillers in the U.S. were literally paying customers to take the fuel away. Enterprise decided it would link the U.S. excess propane and butane to the new demand in Asia—and elsewhere.

By 2013, Enterprise owned nearly 75% of U.S. loading capacity. In 2014 Enterprise and Oiltanking Holdings Americas signed a 50-year contract for Enterprise to be able to use more ship loading and dock space, but Enterprise wanted more than a partnership. By early 2015, Enterprise paid about $5.8 billion for 12 docks on the Houston Ship Channel and another 24 million barrels of storage for oil and refined products.

Others are expanding exporting capacity as well. With Occidental adding 75,000 barrels per day of capacity at its Corpus Christi, Texas, facility recently, and Phillips 66 scheduled to open a 145,000-barrel-per-day terminal at Freeport, Texas later in 2016, there will be even more capacity to ship well beyond the investment of Enterprise. All of this, combined with new ship construction and the expansion of the Panama Canal, makes it possible to further facilitate the flow of U.S. propane to international markets.

Enterprise is also a pioneer in the exporting of American ethane, a fuel that is a key ingredient in plastics manufacturing. Enterprise Products is ramping up usage of what is soon to be world’s largest ethane export facility at Morgan’s Point on the Houston Ship Channel, with two trains and two docks capable of loading about 200,000 barrels per day onto ships. This is significant to propane since there will be that much less ethane here to displace propane as a feedstock for making plastics, even as propane itself is also increasingly exported to foreign markets.

The vision of Enterprise that there would be Asian demand to be met has played out as expected. Asia is now the largest regional destination for U.S. propane with nearly 220,000 barrels per day shipped, slightly more than one-third of total U.S. propane exports in 2015. Transporting large quantities of propane over long distances requires specifically designed refrigerated ships. The largest, most economical class of these ships is the very large gas carrier (VLGC). Until recently only a limited number of VLGC’s with more upright hull designs were able to pass through the Panama Canal lock dimensions, but that all changed with the Panama Canal expansion inaugurated on June 26.

Panama celebrated the first vessel to transit through the 102-year-old Panama Canal on June 26 after a $5.25-billion expansion to allow the canal to accommodate large VLGC’s and other larger vessels. Panama hopes for a trade boost to allow it to be the “Center of the Americas.” With 35 to 40 ships expected to pass through every day, 24 hours a day, seven days a week, Panama hopes to be viewed as the logistic center of the Americas. With 166 reservations already on June 26 as the first larger ship transited, 17 were for liquefied petroleum gas. Panama is excited that the U.S. has become a net exporter of oil and related products to the rest of the world. Previously, size limitations of vessels caused larger ships to either travel all the way around the southern tip of South America or load from smaller vessels after they passed through the canal. This created bottlenecks and challenges as growing demand for propane from the United States continued to increase. Now, with the expansion complete, a trip to Eastern Asia for a larger ship went from 41 days to 25 days! Further, the production of more and more VLGC’s is lowering freight rates due to more competition, and the newest ships are also 17% more fuel-efficient.

The ship-to-ship transfers, where propane is transferred from larger ships to smaller ships to transit the canal, are no longer necessary. The process of multiple product transfers, or one transfer and then propane moving on to Asia on a smaller ship, is over. Not only is propane exporting more cost-effective, the actual sources and destinations are becoming more transparent. With all of the ship transfers that have been taking place at the Panama Canal, EIA has had to decipher confusing information, indicating for example more product shipments to countries such as China and Japan from Panama, a country that does not produce propane. Clearly these shipments were the result of a product transfer from another source, often the U.S. With the end of all the product transfers, we now have much more accurate data from EIA about U.S. propane moving to Asia.

According to data from JBC Energy, propane exports to Asia this year were once close to a record 300,000 barrels per day. Meanwhile, let’s not forget propane exports to Mexico, the Caribbean, and South America doubled between 2010 and 2013, from 88,000 to 198,000 barrels per day. And exports to Europe have increased from 25,000 barrels per day in 2012 to more than 100,000 barrels per day currently. As mentioned earlier, the first quarter of 2016 showed propane moving to all export destinations at 886,000 barrels per day!

Asia is now the largest regional destination for U.S. propane with nearly 220,000 barrels per day, slightly more than one-third of total U.S. propane exports in 2015. Chinese propane dehydrogenation (PDH) plants have contracted 61 million barrels from Enterprise and Targa Resources from third-party traders, in contracts ranging from one to six years. Japan’s largest LPG supplier, Astomos, has contracted 5.9 million barrels from Targa over three years from late 2017, and its purchases 2014 to 2021 are 42 million barrels, mostly from Enterprise.

The completion of the Panama Canal expansion came as Middle East sources were becoming much cheaper than in the past and represented a turning point where Asian companies will be deciding whether they want to try to shift to shorter contract periods. While economics are a key factor, some have pointed out that U.S. supply offers more security than Middle East and Asian sources. The opening of the Panama Canal to larger ships, which cuts journeys almost in half in many cases, combined with lower freight rates as a glut of new vessels come online, will make U.S. propane more attractive. At one time there was an assumption that U.S.-sourced propane would always be cheaper, but that has changed.

There is no doubt shipping capacity from the U.S. has expanded greatly in the past five years as exports were pegged at 884,000 barrels per day in the first quarter of 2016, nearly eight times the rate of exports in 2011. Asian buyers may very likely try to cut their contract periods to six months to a year as lower prices for naphtha (with crude prices lower) and propylene have caused some to be locked into propane when there are better opportunities. Again, the original thought was that U.S. propane would always be oversupplied and cheap.

Recently there have been a greater number of cancellations of shipments from the U.S. due to the lower prices in the Middle East. In many cases, cancellation fees have been paid, since it was still economical to do so and take product from other sources. For now, the economics don’t favor a lot of shipments to Asia in the next couple of months and exports are pegged at 424,000 barrels per day in late September. However, this can once again dramatically change. With the export capacity in place, we must keep in mind just how much can go offshore, very quickly, once again. By the high demand months this winter in the U.S., world demand could be again setting new highs for exports.

As we approach winter 2016-2017, U.S. retailers must understand how much prices in the U.S. can be dramatically affected by exports, or lack of exports. This isn’t 2008, when our capacity to export was limited to about 130,000 barrels per day. After a brutal January and February in 2014, many new rail terminals have been added in the U.S. to help meet domestic supply requirements, but we have not had cold enough weather since then to really test the infrastructure.

Unless we have a lot of rain in early fall, it is doubtful crop drying demand will be above average this season. La Niña conditions could bring about colder-than-normal temperatures, more likely in the second half of the winter season. This, along with exports ramping back up, could test our system and push prices up.

Many wild cards remain as we seek to figure out the direction of propane prices, and exports have become the wildest of the wild cards. Just like the question of whether world supply of crude oil will outstrip demand, there is the question of whether world supply of propane will outstrip demand. On the crude oil side, OPEC and other large producers hold the keys. As of late September, the organization has been more focused on expanding its own market shares and not agreed to cut production. If OPEC has accomplished anything, it has been undercutting crude oil production in countries such as the U.S. The collateral damage to propane has been the lower cost of naphtha and gasoline that it competes with. Most experts, including many world banks and EIA, expect world crude supply and demand to come back into balance in the coming year. Considering this and all the wild cards, we feel there is limited downside for winter 2016-2017. This is a good time to position propane not only for the coming season, but a portion for the next couple of winters as well.

Pat Thornton has been with Mission, Kan.-based Propane Resources since 1996, where he assists retail customers with hedging plans and provides risk-management and supply-planning services. He serves on the Missouri Propane Education and Research Council.