Monday, November 2, 2020

Bob Myers’ career in the propane industry began as many careers begin in the industry—driving a propane truck and delivering fuel. However, during his 25 years with Petrolane, he did leave once to serve in the United States Peace Corps. Upon his return, he settled back to work at the home office, involved with sales as well as purchasing. And that is just the beginning.

In the early years, Myers operated a joint venture for Petrolane with Mobil Oil in the Northeast for three years, which included managing the first tidewater refrigerated propane terminal. Later work included managing supply and distribution for Petrolane in Houston. At that time, the U.S. was still very much a net importer of propane and he imported a great deal of propane for Petrolane from Venezuela. Leading the marketing functions for Petrolane was the next venture for Myers, beginning in 1978. Petrolane was sold to Texas Eastern in 1984 and five years later Texas Eastern was purchased by Quantum Chemical, the parent company of Suburban Propane.

INTRODUCING THE LP GAS "CLEAN FUELS COALITION"

With a two-year “golden parachute” and a wealth of propane industry experience, Myers was asked by a number of “gearheads” to form an organization to promote propane autogas. The group came to be known as the “LP Gas Clean Fuels Coalition.” Amendments to the original Clean Air Act of 1970, the Clean Air Act Amendments (CAAA) of 1990 were introduced in the late 1980s and signed into law by President George H.W. Bush on Nov. 15, 1990. Initially, the singular purpose of the coalition was to see that propane was included in the CAAA. In the initial legislation draft dealing with alternative fuels, propane was not listed. The natural gas, ethanol, and methanol industries made sure they were included but refused to include propane. The National Propane Gas Association (NPGA) had propane autogas as a fifth priority at a time when the top three priorities had consumed all its budget and lobbying time. With a grim prospect of being included in the CAAA, the separate coalition was formed.

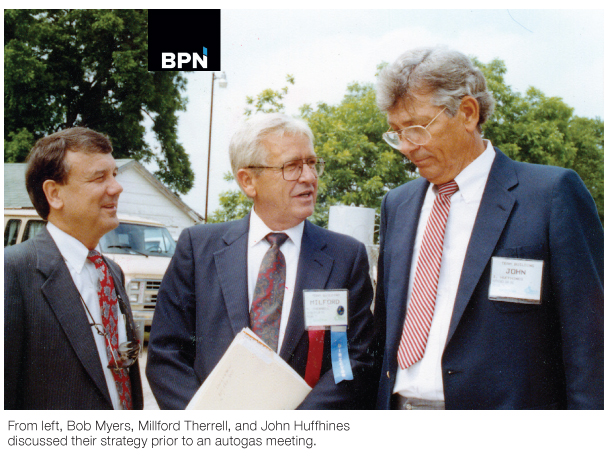

Jerry Schmitt of Ferrellgas was a leader of the effort to start the coalition. Others included Larry Osgood of Phillips 66, Darrel Reifschneider of Manchester Tank (Tenn.), Milford Therrell of Squibb Taylor (Texas), Glenn Miller of Miller’s Bottled Gas (Ky.), Tim and Jay Wood of Northwest Propane (Texas), Gerry Misel of Georgia Gas Distributors (Ga.), Steve Moore of Mutual Propane (Calif.), Curtis Donaldson of Conoco, and Bill Platz of Delta Liquid Energy (Calif.). The incorporation documents for the coalition were completed by Bill Halliburton of Occidental Petroleum (Tulsa), who later served as the group’s first chairman. Myers was the president and treasurer. Rick Roldan, who later served as CEO of NPGA, became executive director of the LP Gas Clean Fuels Coalition later in 1994 under the direction of then chairman, Jim Ferrell, president and chairman of the board of Ferrellgas.

Myers’ agreement to lead the organization was to be “brief,” but ended up lasting about four years. “I had no interest in moving to Washington, D.C., from California, but I spent about half of my time there lobbying for propane,” he said. “I made over 100 personal calls on members of Congress, the Department of Energy (DOE), the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and joint committees of Congress dealing with energy and taxation.” He noted that Jean Mestres of Occidental was extremely helpful in his lobbying efforts. “She provided me a key to her office when I was in town and I had free access to her office anytime day or night,” he said. “I was never charged for use of the phone, fax, or copy machine. Furthermore, she often arranged for me to have dinners and lunches with key Congressional members and always picked up the bill.”

WHY THE PROPANE EDUCATION & RESEARCH COUNCIL (PERC) WAS LAUNCHED

“NPGA’s board always had an ambivalent attitude toward autogas other than forklifts,” Myers said. “After all, it rarely if ever represented more than 5% of total retail volume, a very similar level to what it represents today.” Myers noted, however, that within NPGA there was a group of ardent supporters of autogas, particularly after the Arab crude oil embargoes of the 1970s, who challenged that reasoning. “This group saw all kinds of growth potential in response to shortages of gasoline with high prices,” Myers said. “Rising from this discord was the formation of a group of retail marketers, equipment manufacturers, and distributors that volunteered to collect money based on the sale of each tank and propane mixer to be used in autogas promotion.” According to Myers, NPGA, fearing this group would lead to a fracture in the industry, offered two seats on its board, the only time an end use market ever had specific representation on its board.

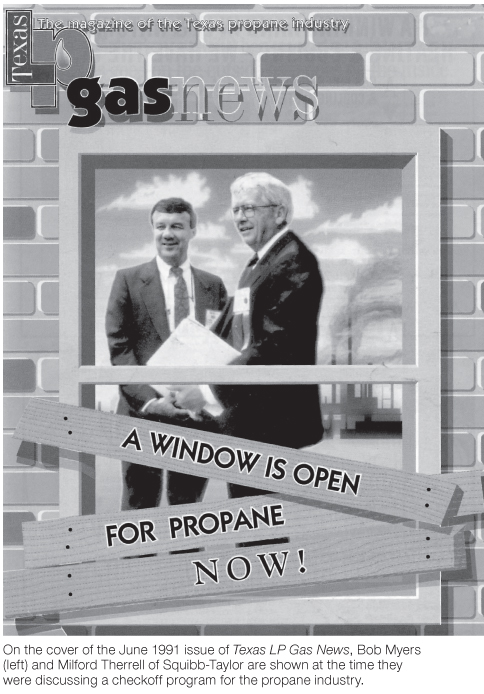

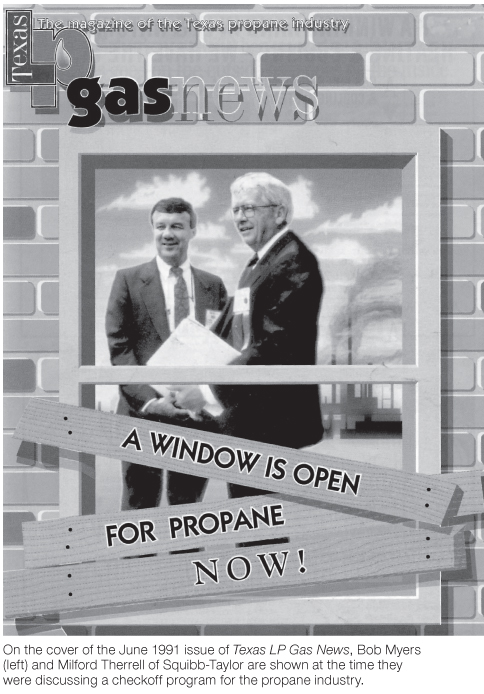

“The Propane Education & Research Council (PERC) is the legacy of NPGA’s reluctance to give more support to the autogas market,” Myers said. He pointed out the work of Milford Therell, who would later be known as the “Father of PERC,” whose efforts along with Glenn Miller promoted the establishment of a propane checkoff program. “I suggested the checkoff program to Milford from my experience growing up on a farm where ‘checkoffs’ were common,” Myers said. “I wrote his first speech on the subject, which he gave to the Kentucky association at Lake Barkley when he became NPGA president in 1991.”

The Propane Education and Research Act (PERA) was passed in 1996 by Congress and PERC was launched in 1997 to assess one-tenth of a cent per gallon of odorized propane sold. For each of five years, PERC was able to add an additional one-tenth of a cent per gallon up to a limit of five-tenths of a cent per gallon. For many of the formative years and beyond, Myers was paid on a retainer or on a contract basis to do a variety of projects for PERC. “In the early years, I helped with many aspects of the establishment of the organization and its procedures. Later, I was involved in many of the research and development areas,” Myers said. “Scouting markets for propane was a key function for me for several years. We studied propane’s potential role in the automotive area, forklift equipment, fuel cells, and a number of other areas.”

Some of the seeds planted came to fruition while others did not. “Certainly, a lot of strides were made in the automotive arena as well as with forklifts. Other areas, such as fuel cells, did not pan out at the time. Propane definitely proved to be a great fuel for fuel cells, but there were a lot of other factors that were big impediments to fuel cells being widely used, including the high cost and a lot of questionability of the longevity of the equipment. With new technology, fuel cells may yet have potential. If so, propane will again be a great fuel for them.”

WORKING WITH THE WORLD AND WESTERN ASSOCIATIONS

In 2000, Myers shuttered his consulting work and moved to Paris, France, where he became the technical director of the World LP Gas Association (WLPGA).

“A big issue for WLPGA was the need for stoves that could be fueled by propane,” Myers said. “For $40 to $50, we could implement a cooking plan for people in developing countries throughout the world so that they would no longer need to use cow dung, trees, grass, or charcoal to fuel the fires to cook and feed their families. This was a huge step forward for these people and literally brought low-income families into the middle class.”

Other organizations such as the United Nations and Cooking for Life were supported by WLPGA in this major effort. Myers noted, though, that large corporations such as Total and Shell did not have operations in a lot of the rural areas of developing countries.

“One of the most powerful presentations I heard during my career was by a lady named Susan McDade. It has been over 20 years, but I still vividly remember not only her name but how she presented the important role LPG can play in breaking the cycle of poverty throughout the world,” he said. “After mingling with company executives during the cocktail hour, she spoke later during the Gala event and confronted some of what she heard over cocktails. She stated that many in the LPG industry have no idea how big a role they play in breaking the cycle of poverty and giving people a better life. She described how in many poor countries, men work day labor jobs such as picking beans, women spend about three hours a day gathering wood for cooking, and daughters often help the mother, which means they are being deprived of an education. She said that the simple addition of a five-kilo stove cuts out three hours a day of gathering wood for the mother and daughters. This then allows the daughters to go to school and can allow the mother a chance to do something that may bring more income to the family.”

In addition to helping families gain more income and education, cooking with propane is much safer, causing fewer fires, and much healthier as the inhalation of smoke is very damaging to people’s lungs. “Many people, both young and old, lost their lives due to the inhalation of too much smoke in the daily cooking process,” Myers said. “Amazingly, a five-kilo stove, a regulator, and a two-burner hot plate can move a family into a much higher standard of living.”

In her remarks, McDade said that several people had commented during the cocktail hour that getting LPG out to the remote rural areas is too difficult. “She reiterated the important role LPG plays in moving these families into a better life,” he added. “And then she mentioned that she had traveled to many remote corners of the world herself and everywhere she goes she can buy a Snickers bar and a can of Coke.” At that point, McDade said, “The Coke is liquid in a can just like LPG. If we need to, let’s talk to the guy who sells the Coke cans; he knows how to distribute them.”

Myers was pleased to be a part of the transition from the World LP-Gas Forum to the World LP-Gas Association. “This transition was led by Jim Ferrell,” Myers said. “The World LP-Gas Forum was an annual gathering of propane leaders from around the world. Jim Ferrell made the case for establishing an association with a defined purpose, staff, and events throughout the year. The World LP-Gas Association still hosts the annual Forum, but there is so much more that can be accomplished with an association of propane leaders from around the world.”

The Western Propane Gas Association presented another opportunity for Myers to solve problems. “California has, as most know, the most stringent laws and regulations in the country for protecting air quality. Navigating the various state agencies including the Air Resources Board and the California Energy Commission can be challenging. Autogas and many types of engines that run on propane represent unique solutions in California due to their low level of emissions.”

AUTOGAS A CONSTANT THROUGHOUT HIS ILLUSTRIOUS CAREER

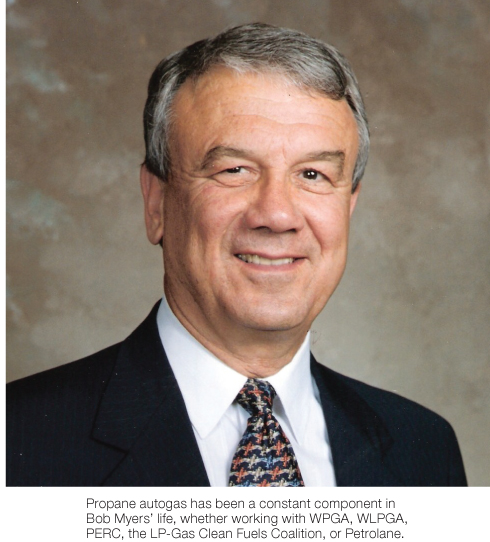

Propane autogas has been a constant component in Myers’ life whether working with WPGA, WLPGA, PERC, the LP-Gas Clean Fuels Coalition, or Petrolane. “The first gallon of propane Petrolane sold went into a vehicle in 1928,” Myers said. “I drove my first propane-powered pickup during a summer job in 1958. It had an IMPCO Imperial 300 Mixer with Bowden cable. Having spent much of my career with marketing responsibilities for increasing sales, I have always favored autogas. It was the market that could, in today’s vernacular, ‘flatten the curve’ between summer and winter demand. When retail plants were mostly dependent on residential heating demand, many actually lost money in summer. Not so when there was an autogas market.”

Myers notes that a Petrolane plant in Casper, Wyo., had a bottle dock, dispenser, and a key lock accessible 24 hours a day. “In some summer months at that plant more volume was delivered from the dispenser than from bobtail deliveries, and with the exception of electricity to run the pump there was no delivery expense,” he added. “At the apex of autogas demand, Petrolane’s autogas volume represented about 25% of total retail demand, and in the summer, it represented over 40%. But autogas required a different mindset than other retail markets. Few had it then, few have it today, in my view.”

Interestingly, Myers notes U.S. autogas usage still doesn’t exceed volumes used in the 1980s. “The technology has definitely improved and the vehicles run much better. There is much more potential for the future,” he said. “But according to NPGA’s Market Facts in 1983, a publication that has since been discontinued, there were 1.1 million propane vehicles utilizing nearly 1.5 billion gallons of what we now call autogas, far more than what is sold today in the U.S.” He notes there can be valid arguments about data collection methods both then and now. “And lest there be a rush to claim the genius of those engaged in those 1983 numbers, keep in mind that most of the vehicles were conversions done under EPA’s Memo 1-A and costing about $1000 each. The quality of many of those conversions was rightfully suspect compared to today, but they did produce the volumes.”

Myers believes autogas would represent a much higher market share if three of the challenges of the past were resolved much faster:

1. There was a lot of lousy equipment jammed on a customer’s vehicle that should never have been taken out of the box.

2 There was a lack of convenient customer service with qualified technicians.

3. There was erratic fuel pricing that destroyed the economics and made no sense to the customer.

“Today, as I did 50 years ago, I believe the growth in the retail market, if any, will in some way be associated with something with a spark plug,” Myers said. “That may be vehicles, forklifts, industrial engines, generator sets, CHP, lawn and gardening equipment, heat pumps, air conditioning—anything with an engine. But resolving the three fundamental issues listed above and a commitment with a different mindset will spell the success or failure of the autogas market in the future. It always has, worldwide.” – Pat Thornton

In the early years, Myers operated a joint venture for Petrolane with Mobil Oil in the Northeast for three years, which included managing the first tidewater refrigerated propane terminal. Later work included managing supply and distribution for Petrolane in Houston. At that time, the U.S. was still very much a net importer of propane and he imported a great deal of propane for Petrolane from Venezuela. Leading the marketing functions for Petrolane was the next venture for Myers, beginning in 1978. Petrolane was sold to Texas Eastern in 1984 and five years later Texas Eastern was purchased by Quantum Chemical, the parent company of Suburban Propane.

INTRODUCING THE LP GAS "CLEAN FUELS COALITION"

With a two-year “golden parachute” and a wealth of propane industry experience, Myers was asked by a number of “gearheads” to form an organization to promote propane autogas. The group came to be known as the “LP Gas Clean Fuels Coalition.” Amendments to the original Clean Air Act of 1970, the Clean Air Act Amendments (CAAA) of 1990 were introduced in the late 1980s and signed into law by President George H.W. Bush on Nov. 15, 1990. Initially, the singular purpose of the coalition was to see that propane was included in the CAAA. In the initial legislation draft dealing with alternative fuels, propane was not listed. The natural gas, ethanol, and methanol industries made sure they were included but refused to include propane. The National Propane Gas Association (NPGA) had propane autogas as a fifth priority at a time when the top three priorities had consumed all its budget and lobbying time. With a grim prospect of being included in the CAAA, the separate coalition was formed.

Jerry Schmitt of Ferrellgas was a leader of the effort to start the coalition. Others included Larry Osgood of Phillips 66, Darrel Reifschneider of Manchester Tank (Tenn.), Milford Therrell of Squibb Taylor (Texas), Glenn Miller of Miller’s Bottled Gas (Ky.), Tim and Jay Wood of Northwest Propane (Texas), Gerry Misel of Georgia Gas Distributors (Ga.), Steve Moore of Mutual Propane (Calif.), Curtis Donaldson of Conoco, and Bill Platz of Delta Liquid Energy (Calif.). The incorporation documents for the coalition were completed by Bill Halliburton of Occidental Petroleum (Tulsa), who later served as the group’s first chairman. Myers was the president and treasurer. Rick Roldan, who later served as CEO of NPGA, became executive director of the LP Gas Clean Fuels Coalition later in 1994 under the direction of then chairman, Jim Ferrell, president and chairman of the board of Ferrellgas.

Myers’ agreement to lead the organization was to be “brief,” but ended up lasting about four years. “I had no interest in moving to Washington, D.C., from California, but I spent about half of my time there lobbying for propane,” he said. “I made over 100 personal calls on members of Congress, the Department of Energy (DOE), the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and joint committees of Congress dealing with energy and taxation.” He noted that Jean Mestres of Occidental was extremely helpful in his lobbying efforts. “She provided me a key to her office when I was in town and I had free access to her office anytime day or night,” he said. “I was never charged for use of the phone, fax, or copy machine. Furthermore, she often arranged for me to have dinners and lunches with key Congressional members and always picked up the bill.”

WHY THE PROPANE EDUCATION & RESEARCH COUNCIL (PERC) WAS LAUNCHED

“NPGA’s board always had an ambivalent attitude toward autogas other than forklifts,” Myers said. “After all, it rarely if ever represented more than 5% of total retail volume, a very similar level to what it represents today.” Myers noted, however, that within NPGA there was a group of ardent supporters of autogas, particularly after the Arab crude oil embargoes of the 1970s, who challenged that reasoning. “This group saw all kinds of growth potential in response to shortages of gasoline with high prices,” Myers said. “Rising from this discord was the formation of a group of retail marketers, equipment manufacturers, and distributors that volunteered to collect money based on the sale of each tank and propane mixer to be used in autogas promotion.” According to Myers, NPGA, fearing this group would lead to a fracture in the industry, offered two seats on its board, the only time an end use market ever had specific representation on its board.

“The Propane Education & Research Council (PERC) is the legacy of NPGA’s reluctance to give more support to the autogas market,” Myers said. He pointed out the work of Milford Therell, who would later be known as the “Father of PERC,” whose efforts along with Glenn Miller promoted the establishment of a propane checkoff program. “I suggested the checkoff program to Milford from my experience growing up on a farm where ‘checkoffs’ were common,” Myers said. “I wrote his first speech on the subject, which he gave to the Kentucky association at Lake Barkley when he became NPGA president in 1991.”

The Propane Education and Research Act (PERA) was passed in 1996 by Congress and PERC was launched in 1997 to assess one-tenth of a cent per gallon of odorized propane sold. For each of five years, PERC was able to add an additional one-tenth of a cent per gallon up to a limit of five-tenths of a cent per gallon. For many of the formative years and beyond, Myers was paid on a retainer or on a contract basis to do a variety of projects for PERC. “In the early years, I helped with many aspects of the establishment of the organization and its procedures. Later, I was involved in many of the research and development areas,” Myers said. “Scouting markets for propane was a key function for me for several years. We studied propane’s potential role in the automotive area, forklift equipment, fuel cells, and a number of other areas.”

Some of the seeds planted came to fruition while others did not. “Certainly, a lot of strides were made in the automotive arena as well as with forklifts. Other areas, such as fuel cells, did not pan out at the time. Propane definitely proved to be a great fuel for fuel cells, but there were a lot of other factors that were big impediments to fuel cells being widely used, including the high cost and a lot of questionability of the longevity of the equipment. With new technology, fuel cells may yet have potential. If so, propane will again be a great fuel for them.”

WORKING WITH THE WORLD AND WESTERN ASSOCIATIONS

In 2000, Myers shuttered his consulting work and moved to Paris, France, where he became the technical director of the World LP Gas Association (WLPGA).

“A big issue for WLPGA was the need for stoves that could be fueled by propane,” Myers said. “For $40 to $50, we could implement a cooking plan for people in developing countries throughout the world so that they would no longer need to use cow dung, trees, grass, or charcoal to fuel the fires to cook and feed their families. This was a huge step forward for these people and literally brought low-income families into the middle class.”

Other organizations such as the United Nations and Cooking for Life were supported by WLPGA in this major effort. Myers noted, though, that large corporations such as Total and Shell did not have operations in a lot of the rural areas of developing countries.

“One of the most powerful presentations I heard during my career was by a lady named Susan McDade. It has been over 20 years, but I still vividly remember not only her name but how she presented the important role LPG can play in breaking the cycle of poverty throughout the world,” he said. “After mingling with company executives during the cocktail hour, she spoke later during the Gala event and confronted some of what she heard over cocktails. She stated that many in the LPG industry have no idea how big a role they play in breaking the cycle of poverty and giving people a better life. She described how in many poor countries, men work day labor jobs such as picking beans, women spend about three hours a day gathering wood for cooking, and daughters often help the mother, which means they are being deprived of an education. She said that the simple addition of a five-kilo stove cuts out three hours a day of gathering wood for the mother and daughters. This then allows the daughters to go to school and can allow the mother a chance to do something that may bring more income to the family.”

In addition to helping families gain more income and education, cooking with propane is much safer, causing fewer fires, and much healthier as the inhalation of smoke is very damaging to people’s lungs. “Many people, both young and old, lost their lives due to the inhalation of too much smoke in the daily cooking process,” Myers said. “Amazingly, a five-kilo stove, a regulator, and a two-burner hot plate can move a family into a much higher standard of living.”

In her remarks, McDade said that several people had commented during the cocktail hour that getting LPG out to the remote rural areas is too difficult. “She reiterated the important role LPG plays in moving these families into a better life,” he added. “And then she mentioned that she had traveled to many remote corners of the world herself and everywhere she goes she can buy a Snickers bar and a can of Coke.” At that point, McDade said, “The Coke is liquid in a can just like LPG. If we need to, let’s talk to the guy who sells the Coke cans; he knows how to distribute them.”

Myers was pleased to be a part of the transition from the World LP-Gas Forum to the World LP-Gas Association. “This transition was led by Jim Ferrell,” Myers said. “The World LP-Gas Forum was an annual gathering of propane leaders from around the world. Jim Ferrell made the case for establishing an association with a defined purpose, staff, and events throughout the year. The World LP-Gas Association still hosts the annual Forum, but there is so much more that can be accomplished with an association of propane leaders from around the world.”

The Western Propane Gas Association presented another opportunity for Myers to solve problems. “California has, as most know, the most stringent laws and regulations in the country for protecting air quality. Navigating the various state agencies including the Air Resources Board and the California Energy Commission can be challenging. Autogas and many types of engines that run on propane represent unique solutions in California due to their low level of emissions.”

AUTOGAS A CONSTANT THROUGHOUT HIS ILLUSTRIOUS CAREER

Propane autogas has been a constant component in Myers’ life whether working with WPGA, WLPGA, PERC, the LP-Gas Clean Fuels Coalition, or Petrolane. “The first gallon of propane Petrolane sold went into a vehicle in 1928,” Myers said. “I drove my first propane-powered pickup during a summer job in 1958. It had an IMPCO Imperial 300 Mixer with Bowden cable. Having spent much of my career with marketing responsibilities for increasing sales, I have always favored autogas. It was the market that could, in today’s vernacular, ‘flatten the curve’ between summer and winter demand. When retail plants were mostly dependent on residential heating demand, many actually lost money in summer. Not so when there was an autogas market.”

Myers notes that a Petrolane plant in Casper, Wyo., had a bottle dock, dispenser, and a key lock accessible 24 hours a day. “In some summer months at that plant more volume was delivered from the dispenser than from bobtail deliveries, and with the exception of electricity to run the pump there was no delivery expense,” he added. “At the apex of autogas demand, Petrolane’s autogas volume represented about 25% of total retail demand, and in the summer, it represented over 40%. But autogas required a different mindset than other retail markets. Few had it then, few have it today, in my view.”

Interestingly, Myers notes U.S. autogas usage still doesn’t exceed volumes used in the 1980s. “The technology has definitely improved and the vehicles run much better. There is much more potential for the future,” he said. “But according to NPGA’s Market Facts in 1983, a publication that has since been discontinued, there were 1.1 million propane vehicles utilizing nearly 1.5 billion gallons of what we now call autogas, far more than what is sold today in the U.S.” He notes there can be valid arguments about data collection methods both then and now. “And lest there be a rush to claim the genius of those engaged in those 1983 numbers, keep in mind that most of the vehicles were conversions done under EPA’s Memo 1-A and costing about $1000 each. The quality of many of those conversions was rightfully suspect compared to today, but they did produce the volumes.”

Myers believes autogas would represent a much higher market share if three of the challenges of the past were resolved much faster:

1. There was a lot of lousy equipment jammed on a customer’s vehicle that should never have been taken out of the box.

2 There was a lack of convenient customer service with qualified technicians.

3. There was erratic fuel pricing that destroyed the economics and made no sense to the customer.

“Today, as I did 50 years ago, I believe the growth in the retail market, if any, will in some way be associated with something with a spark plug,” Myers said. “That may be vehicles, forklifts, industrial engines, generator sets, CHP, lawn and gardening equipment, heat pumps, air conditioning—anything with an engine. But resolving the three fundamental issues listed above and a commitment with a different mindset will spell the success or failure of the autogas market in the future. It always has, worldwide.” – Pat Thornton