Thursday, June 9, 2016

By Richard Fredenburg … Most states have some form of legal requirement that propane installations meet certain standards, and more often than not, the standard is NFPA 58, the “LP-Gas Code.” Our inspection team received code enforcement training that might shed some light on what is expected of us as enforcers and what is expected of those we inspect. This article will point out some of the similarities and differences.

The training was provided by Reed Jarvis, a retired fire inspector, who pointed out that buildings and installations have to be built or installed to meet all of the code requirements. But an inspector is not required by law to verify that all requirements are met when he does an inspection. If an installation of a propane system fails to meet all of the requirements, it could be that Murphy’s Law will kick in and those few, seemingly minor, missed requirements will cause a release of product. For an inspector to always look at every requirement would be a staggering task. But, to be fair, he should be consistent in what he looks at so each company is treated equally.

Each inspector is likely to take a slightly different approach on an inspection. They are human and have varying areas of concern. For example, think of all the things an inspector could look at when he is at a propane bulk plant. If he had to verify every requirement, he would insist on checking the U-1 data sheet for every bulk tank and small tank installed there. Instead, he looks at the nameplate and, if all is proper there, he accepts that the tank is properly built. The same goes for valves and other components that have to meet UL, ANSI, and ASTM requirements. Examining all of the documentation would be tremendously time-consuming for the inspector. It would also be a challenge for the company to maintain the documentation and have it available for the inspector.

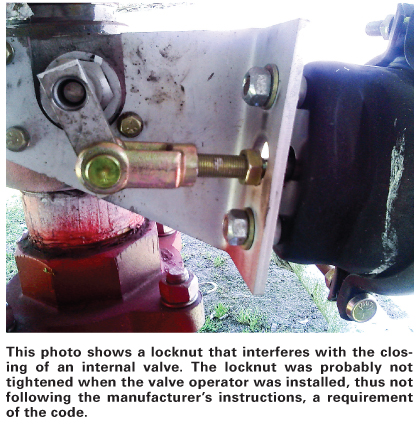

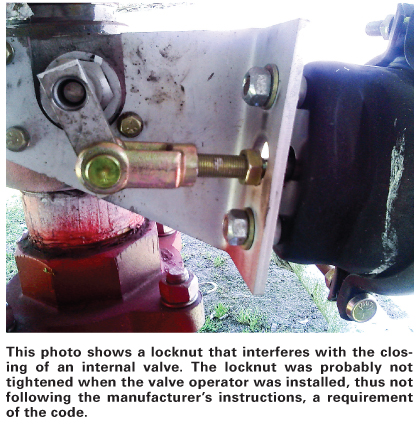

Installers and dealers know by training that they have to buy components and materials that meet the requirements stated in the code and install them according to requirements. We verify a lot of that. But to verify the system in its entirety, the company would have to break apart some assemblies to allow the inspector to see everything. For instance, the piping would have to be disassembled for an inspector to verify that Schedule 80 pipe was used instead of Schedule 40 pipe. Regular inspections to that level would be expensive for dealers and cause considerable down time.

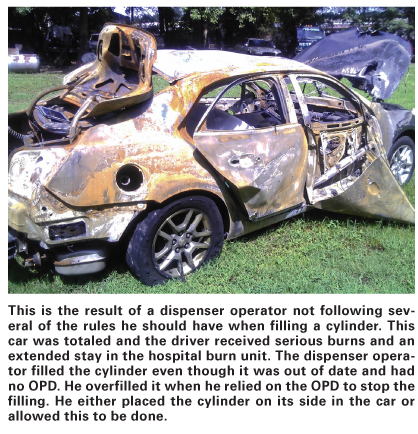

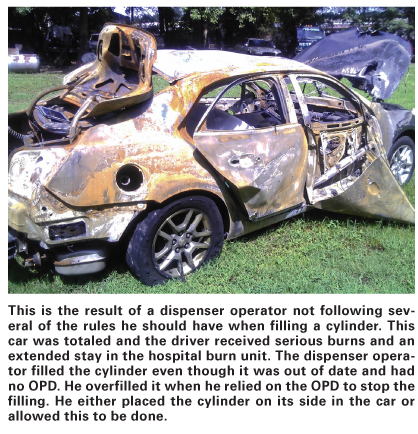

The same type of thing happens with operations. A dispenser operator needs to do a proper visual inspection of every cylinder before he fills it. However, each cylinder has a different life story to tell, so generalizations about whether or not a cylinder is safe to fill based on a casual glance at it may allow a critical failing to go unnoticed.

An inspector is there to observe for only a short time and will likely not see the variety of cylinder conditions presented.

In its recent magazine, our North Carolina state propane association had a picture of a cylinder that was filled without removing the sleeve. When it was filled again a week later, the sleeve was removed and a layer of the steel came away as rust with the sleeve. The amount of corrosion present obviously didn’t occur in just one week or one month. That was not seen at the previous fill because the sleeve was not removed. That example, plus some fire incidents we investigated last year where out-of-date cylinders were filled, point out the real danger that filling compromised containers poses, and the important role dispenser operators have concerning tank safety every time they fill one.

And it’s not just cylinders: Every tank at a residence has to be examined before filling because inspectors will never get to all of those locations. Marketers have to be painstaking when they install the system and each time they fill the tank. I believe that this industry will be even safer if marketers instill a culture of safety in their employees.

Our inspection forms do not have every requirement listed. To do so would make each inspection form many pages long.

We have different forms for each type of inspection. Rather than list what would effectively be the entire “LP-Gas Code” plus some state rules on every form, we categorize forms into bulk plants, dispensers, trucks, and miscellaneous. Miscellaneous includes domestic, cylinder exchange, food truck, and some observed violations. That makes each form manageable. We include the important items and common violations we find and provide a place to note “other” violations not listed. Inspectors are trained on the code and will sometimes include relatively rare violations not included on the list but in the code.

The different inspection forms are part of the way we assist inspectors to be uniform in their inspections. The items listed tend to focus the inspectors’ attention on the important items; however, they don’t limit their observations to just those items.

The recent training pointed out that we don’t really have the option of allowing a violation to continue. But, to require it to be repaired immediately would impose an unrealistic expectation. We shouldn’t say to fix it by a certain date, but we can say when we will return to do a follow-up inspection, expecting corrections to be complete.

I also made a change in the way I reply to extension requests. Instead of saying the corrections do not have to be made until a certain date, I note that the inspector will not return for the follow-up inspection until a certain date. I don’t want to make a statement that leaving the violations uncorrected is OK. It is in everyone’s best interest to correct violations as quickly as possible. Also, I don’t want any liability for us saying that a violation may continue.

We encourage the idea of meeting all rules each time a system is installed or a container is filled. We look at a sampling of some types of sites and watch some of the filling operations, hoping that knowing we are watching will encourage marketers to be vigilant. But, it is marketers establishing and encouraging a culture of safety among their employees that will carry the biggest impact on improving safety.

[My thanks to Donald Godfrey, chair of the North Carolina Propane Gas Association Education/Safety Committee, for the “culture of safety” concept and to Reed Jarvis for the training.]

Richard Fredenburg is LP-gas engineer for the North Carolina Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Standards Division.

The training was provided by Reed Jarvis, a retired fire inspector, who pointed out that buildings and installations have to be built or installed to meet all of the code requirements. But an inspector is not required by law to verify that all requirements are met when he does an inspection. If an installation of a propane system fails to meet all of the requirements, it could be that Murphy’s Law will kick in and those few, seemingly minor, missed requirements will cause a release of product. For an inspector to always look at every requirement would be a staggering task. But, to be fair, he should be consistent in what he looks at so each company is treated equally.

Each inspector is likely to take a slightly different approach on an inspection. They are human and have varying areas of concern. For example, think of all the things an inspector could look at when he is at a propane bulk plant. If he had to verify every requirement, he would insist on checking the U-1 data sheet for every bulk tank and small tank installed there. Instead, he looks at the nameplate and, if all is proper there, he accepts that the tank is properly built. The same goes for valves and other components that have to meet UL, ANSI, and ASTM requirements. Examining all of the documentation would be tremendously time-consuming for the inspector. It would also be a challenge for the company to maintain the documentation and have it available for the inspector.

Installers and dealers know by training that they have to buy components and materials that meet the requirements stated in the code and install them according to requirements. We verify a lot of that. But to verify the system in its entirety, the company would have to break apart some assemblies to allow the inspector to see everything. For instance, the piping would have to be disassembled for an inspector to verify that Schedule 80 pipe was used instead of Schedule 40 pipe. Regular inspections to that level would be expensive for dealers and cause considerable down time.

The same type of thing happens with operations. A dispenser operator needs to do a proper visual inspection of every cylinder before he fills it. However, each cylinder has a different life story to tell, so generalizations about whether or not a cylinder is safe to fill based on a casual glance at it may allow a critical failing to go unnoticed.

An inspector is there to observe for only a short time and will likely not see the variety of cylinder conditions presented.

In its recent magazine, our North Carolina state propane association had a picture of a cylinder that was filled without removing the sleeve. When it was filled again a week later, the sleeve was removed and a layer of the steel came away as rust with the sleeve. The amount of corrosion present obviously didn’t occur in just one week or one month. That was not seen at the previous fill because the sleeve was not removed. That example, plus some fire incidents we investigated last year where out-of-date cylinders were filled, point out the real danger that filling compromised containers poses, and the important role dispenser operators have concerning tank safety every time they fill one.

And it’s not just cylinders: Every tank at a residence has to be examined before filling because inspectors will never get to all of those locations. Marketers have to be painstaking when they install the system and each time they fill the tank. I believe that this industry will be even safer if marketers instill a culture of safety in their employees.

Our inspection forms do not have every requirement listed. To do so would make each inspection form many pages long.

We have different forms for each type of inspection. Rather than list what would effectively be the entire “LP-Gas Code” plus some state rules on every form, we categorize forms into bulk plants, dispensers, trucks, and miscellaneous. Miscellaneous includes domestic, cylinder exchange, food truck, and some observed violations. That makes each form manageable. We include the important items and common violations we find and provide a place to note “other” violations not listed. Inspectors are trained on the code and will sometimes include relatively rare violations not included on the list but in the code.

The different inspection forms are part of the way we assist inspectors to be uniform in their inspections. The items listed tend to focus the inspectors’ attention on the important items; however, they don’t limit their observations to just those items.

The recent training pointed out that we don’t really have the option of allowing a violation to continue. But, to require it to be repaired immediately would impose an unrealistic expectation. We shouldn’t say to fix it by a certain date, but we can say when we will return to do a follow-up inspection, expecting corrections to be complete.

I also made a change in the way I reply to extension requests. Instead of saying the corrections do not have to be made until a certain date, I note that the inspector will not return for the follow-up inspection until a certain date. I don’t want to make a statement that leaving the violations uncorrected is OK. It is in everyone’s best interest to correct violations as quickly as possible. Also, I don’t want any liability for us saying that a violation may continue.

We encourage the idea of meeting all rules each time a system is installed or a container is filled. We look at a sampling of some types of sites and watch some of the filling operations, hoping that knowing we are watching will encourage marketers to be vigilant. But, it is marketers establishing and encouraging a culture of safety among their employees that will carry the biggest impact on improving safety.

[My thanks to Donald Godfrey, chair of the North Carolina Propane Gas Association Education/Safety Committee, for the “culture of safety” concept and to Reed Jarvis for the training.]

Richard Fredenburg is LP-gas engineer for the North Carolina Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Standards Division.