Wednesday, July 6, 2016

On Tuesday, June 26, 2016, the Panama Canal Authority opened a third set of locks that will double its capacity and allow the transit of larger ships, the first such expansion since the canal was completed in 1914, notes the Energy Information Administration (EIA). However, because of the economics of shipping, trade patterns, and the types of ships used to transport crude and petroleum products, the latest expansion is expected to have limited effect on most petroleum markets.

It should be noted, however, that the new canal expansion could be expected to improve the logistics of U.S. propane exports. Previously, the canal’s size restrictions required ship-to-ship transfers, which created bottlenecks for U.S. propane exports to Asian markets. The new larger Panama Canal locks will allow a majority of very large gas carriers (VLGCs), the type of ship that carries propane and other hydrocarbon gas liquids, to transit, likely reducing or perhaps eliminating the need for ship-to-ship transfers.

EIA explains that the economics of shipping crude oil and petroleum products improve as the ship size and the distance traveled increase. Crude oil is typically loaded on vessels classified as very large crude carriers, VLCCs, or ultra-large crude carriers, ULCCs, each of which, when fully laden, is too large to transit the new locks of the Panama Canal. Petroleum products are typically loaded on smaller vessels, some of which can transit both the existing and new locks, depending on the ship’s hull design and draft. This means that most of the petroleum-related traffic through the canal will continue to be petroleum products, rather than crude oil.

In 2015, most of the petroleum-related traffic on the canal moved southbound, from the Atlantic to the Pacific, with diesel fuel and gasoline accounting for the largest share of traffic at 9.5 million long tons (a unit of measure for cargo volume equal to 2240 U.S. pounds) and 9.1 million long tons, respectively. Largely because of ship size restrictions, crude oil traffic was significantly smaller, and almost equal in both directions with 3 million long tons going southbound versus 2.6 million long tons moving northbound.

U.S. exports of petroleum products from the Gulf Coast to the west coast of South America, with destinations for Chile, Ecuador, and Peru, likely transit the Panama Canal. With South American refining capacity trailing regional demand—which has expanded in countries such as Chile and Peru because of commodity-led economic growth—U.S. Gulf Coast refineries have increased exports of diesel and gasoline to these markets.

In 2015, the U.S. Gulf Coast exported a combined 159,000 bbld of distillate to Chile, Ecuador, and Peru, an increase of 32,000 bbld compared to 2014. The U.S. Gulf Coast also exported 63,000 bbld of motor gasoline to the three nations in 2015, an increase of 21,000 bbld over 2014. However, lower commodity prices in recent years could reduce economic growth in these countries and lessen demand for petroleum products from the Gulf Coast, EIA comments.

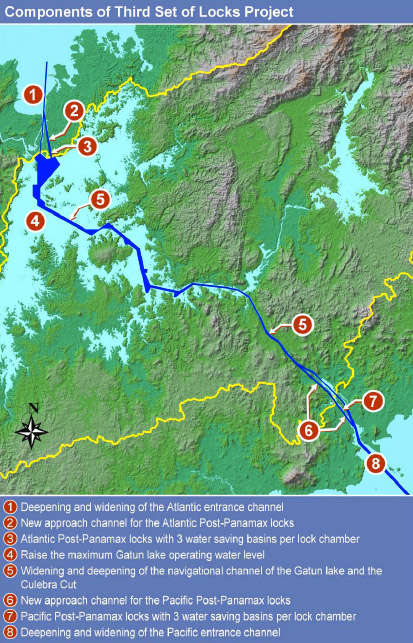

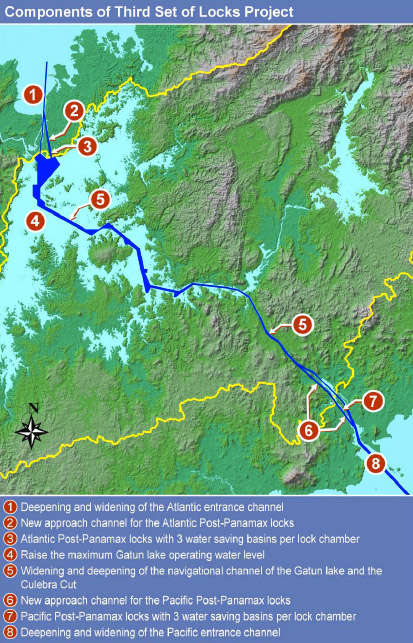

Entrances to the Panama Canal are near the cities of Colon on the Atlantic Ocean to the north, and Panama City on the Pacific Ocean to the south. The canal expansion involved deepening and widening certain portions of the existing canal and constructing a larger third set of locks. Unlike the old lock system, which has two lanes of traffic side-by-side, the third set of locks has one large lane and allows four transits a day, compared to 25 daily transits using the older lock system. The wider and deeper navigation channels and larger locks allow for the transit of larger vessels through the canal. While the old lock systems capped tanker capacity at about 300,000 to 500,000 bbl of petroleum products, the newer lock systems can accommodate vessels with estimated capacity of 400,000 to 600,000 bbl.

The latest canal expansion comes at a time when petroleum product tanker rates are at their lowest levels since 2009, in part because of elevated global product inventories. From January through May 2016, rates for a shipment of product from the Arabian Gulf to Japan, a general indicator for global tanker rates, have averaged about $21 a metric ton, after averaging more than $30 a metric ton in 2015. Lower prices for bunker fuel, as a result of lower oil prices, reduce a ship owner’s cost for a longer, less direct, journey and result in lower freight rates paid by the shipper.

(Photo: NBC News, Locks Diagram: Wikipedia)

It should be noted, however, that the new canal expansion could be expected to improve the logistics of U.S. propane exports. Previously, the canal’s size restrictions required ship-to-ship transfers, which created bottlenecks for U.S. propane exports to Asian markets. The new larger Panama Canal locks will allow a majority of very large gas carriers (VLGCs), the type of ship that carries propane and other hydrocarbon gas liquids, to transit, likely reducing or perhaps eliminating the need for ship-to-ship transfers.

EIA explains that the economics of shipping crude oil and petroleum products improve as the ship size and the distance traveled increase. Crude oil is typically loaded on vessels classified as very large crude carriers, VLCCs, or ultra-large crude carriers, ULCCs, each of which, when fully laden, is too large to transit the new locks of the Panama Canal. Petroleum products are typically loaded on smaller vessels, some of which can transit both the existing and new locks, depending on the ship’s hull design and draft. This means that most of the petroleum-related traffic through the canal will continue to be petroleum products, rather than crude oil.

In 2015, most of the petroleum-related traffic on the canal moved southbound, from the Atlantic to the Pacific, with diesel fuel and gasoline accounting for the largest share of traffic at 9.5 million long tons (a unit of measure for cargo volume equal to 2240 U.S. pounds) and 9.1 million long tons, respectively. Largely because of ship size restrictions, crude oil traffic was significantly smaller, and almost equal in both directions with 3 million long tons going southbound versus 2.6 million long tons moving northbound.

U.S. exports of petroleum products from the Gulf Coast to the west coast of South America, with destinations for Chile, Ecuador, and Peru, likely transit the Panama Canal. With South American refining capacity trailing regional demand—which has expanded in countries such as Chile and Peru because of commodity-led economic growth—U.S. Gulf Coast refineries have increased exports of diesel and gasoline to these markets.

In 2015, the U.S. Gulf Coast exported a combined 159,000 bbld of distillate to Chile, Ecuador, and Peru, an increase of 32,000 bbld compared to 2014. The U.S. Gulf Coast also exported 63,000 bbld of motor gasoline to the three nations in 2015, an increase of 21,000 bbld over 2014. However, lower commodity prices in recent years could reduce economic growth in these countries and lessen demand for petroleum products from the Gulf Coast, EIA comments.

Entrances to the Panama Canal are near the cities of Colon on the Atlantic Ocean to the north, and Panama City on the Pacific Ocean to the south. The canal expansion involved deepening and widening certain portions of the existing canal and constructing a larger third set of locks. Unlike the old lock system, which has two lanes of traffic side-by-side, the third set of locks has one large lane and allows four transits a day, compared to 25 daily transits using the older lock system. The wider and deeper navigation channels and larger locks allow for the transit of larger vessels through the canal. While the old lock systems capped tanker capacity at about 300,000 to 500,000 bbl of petroleum products, the newer lock systems can accommodate vessels with estimated capacity of 400,000 to 600,000 bbl.

The latest canal expansion comes at a time when petroleum product tanker rates are at their lowest levels since 2009, in part because of elevated global product inventories. From January through May 2016, rates for a shipment of product from the Arabian Gulf to Japan, a general indicator for global tanker rates, have averaged about $21 a metric ton, after averaging more than $30 a metric ton in 2015. Lower prices for bunker fuel, as a result of lower oil prices, reduce a ship owner’s cost for a longer, less direct, journey and result in lower freight rates paid by the shipper.

(Photo: NBC News, Locks Diagram: Wikipedia)