Friday, July 12, 2019

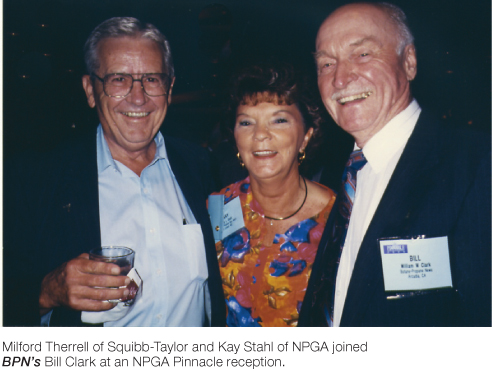

To mark the 80th anniversary of BPN, we are reprinting here a comprehensive history of the magazine that first appeared in 1999. Written by then-publisher Bill Clark, this tells the story of BPN’s first 60 years. At the time he wrote this in January 1999, Clark had been with BPN since the end of World War II and had owned the magazine since 1969.

Nineteen-ninety-nine marks Butane-Propane News’ 60th year. Or is it really its 68th? Or, if you are one to literally believe the volume number published on this page, only its 31st?

Nineteen-ninety-nine marks Butane-Propane News’ 60th year. Or is it really its 68th? Or, if you are one to literally believe the volume number published on this page, only its 31st?

All three ages have validity. BPN was actually born in 1931—68 years ago—as a section in a magazine, long defunct, called Western Gas. In fact, for many years after we became a separate magazine our motto was, “Headquarters for LP-Gas Information Since 1931.” The slogan was factually accurate for a number of years, but as the industry grew and matured, and as NPGA’s role expanded, we voluntarily relinquished our claim to the distinction. The association is now the true “headquarters.”

As for the volume number 31, that refers to the date when my wife and I took over ownership. Since the magazine had already been declared moribund by its previous owners, we decided to start afresh at Vol. 1.

Any way to calculate its age, BPN has been a part of the industry from the time propane marketing was beginning to emerge as a viable member of the family of fuels.

GOING BACK TO THE 1920s

BPN’s roots are traceable to the mid-twenties—it seems to me it was 1925; while that date might not be accurate, it’s close—when a native Oklahoman named Jay Jenkins moved to Southern California and launched Western Gas. In those days, when air travel was virtually non-existent and long-distance trucking was in its infancy, the Western states were little more than an enclave. The Rocky Mountains were a major barrier to the east-west commerce, so the Western markets were primarily provincial; thus regional

publications were a healthy and growing industry.

Western Gas was conceived as strictly a gas utility

Western Gas was conceived as strictly a gas utility

publication, but it didn’t remain so forever.

As for the LPG business, it was largely centered in the mid-Eastern seaboard area, the product itself having first been stripped out of a mixture of hydrocarbons at a plant in Sistersville, W. Va. and having been introduced to the public as a residential fuel in 1912 in Pittsburgh. Growth was slow, even in the East. But in the 1920s two of the true pioneers in the business, the Kerr cousins, moved to Southern California and organized a business known as Rockgas. At about the same time, Western producers were also becoming interested in marketing the product.

And so was at least one gas utility, Southern Counties Gas Co., now a part of Southern California Gas Co. SoCounties saw the youngster as a means of entrée into markets beyond the reach of the gas mains, so about 1930 it began an active program of development. And Jay Jenkins, the astute business man, perceived the situation as an opportunity to expand his magazine’s readership and advertising potential. Thus was Butane-Propane News born as a section in Western Gas.

In those days, the product was generally delivered to market as a mixture, which was called “butane-propane.” Hence the rather clumsy name of the new section, which we and the former owners have chosen to perpetuate because of the magazine’s long-standing reputation, even though most of the marketed product is now predominantly propane.

As the decade of the’’30s wore on, transcontinental communications and travel became steadily more rapid, and the hump of the Rockies no longer posed a significant barrier to commerce. So, in 1937, Jay Jenkins decided to take Western Gas national, challenging the two New York-based magazines, the venerable American Gas Journal and the well-established Gas Age. He dropped the name “Western,” so the name became simply GAS. (Parenthetically, none of the three magazines is still in existence.)

Then, in 1939, he decided to sever BPN’s umbilical cord, making it a magazine in its own right. His timing, which under ordinary situations would have been excellent, proved a bit premature, as the entry of the U.S. into World War II two and a half years later stunted the growth of both magazines until Japan surrendered in 1945.

Paper was short, ink was probably short, everything that manufacturers produced was diverted to the war effort. Many consumer products were discontinued, prices were strictly controlled, and advertising suffered. Yet with government regulations proliferating (sound familiar?), it gave BPN an opportunity to play an important role in publishing and interpreting the often onerous and frequently confusing rules.

Postwar, the magazine proved a perfect fit for a rapidly growing industry. It was the age of moms-and-pops, with thousands of brand new entrepreneurs springing up every year. Many borrowed a few bucks, bought a truck, found a producer who would give them a helping hand, and began peddling cylinders around the countryside. Many others went into the bulk delivery business with money loaned by the banks or by a relative or two.

Most of them needed education in handling the product. So BPN expanded its role as “Headquarters for LP-gas Information.” It was published in the old Reader’s Digest size, which fit neatly into a truck’s glove compartment. And it became in effect a traveling library for the owner/driver. The size proved very popular among the young entrepreneurs. It featured a “Letters” department, which printed and answered myriad technical questions, most of which were rather elementary, since most of the growing corps of marketers were neither chemists nor engineers. Over the years this department was handled by two “technical editors,” both very capable industry engineers. Some old-timers might still remember Lester Luxon, who fulfilled the role after the first man died. At the time, Luxon was chief engineer for Algas, which was then located in Southern California.

The company also published the “Handbook Butane-Propane Gases,” which proved very popular and went into several printings and updates during its life span. Again, this strengthened the magazine’s reputation as headquarters for

LP-gas information.

The late 1940s and the early 1950s were halcyon years for both GAS and Butane-Propane News. Both industries were roaring ahead with rapid growth—in the case of LPG, its growth reportedly matched that of the electronics industry. Advertising revenues zoomed. The tank business, in particular, was soaring. It seemed as if every street corner in Texas had sprouted a tank manufacturer.

Business was so good that Jay Jenkins, riding high, decreed that any company that did not buy two-page spreads would not find its ad in the front of the magazines (which at that time was a preferred position). Companies’ annual budgets of 24 full pages were not uncommon. In 1955, their peak year, both GAS and Butane-Propane News ran more than 1200 pages of advertising—100 pages per month—and the folio of many issues totaled 200 pages, ads and editorial combined, or more.

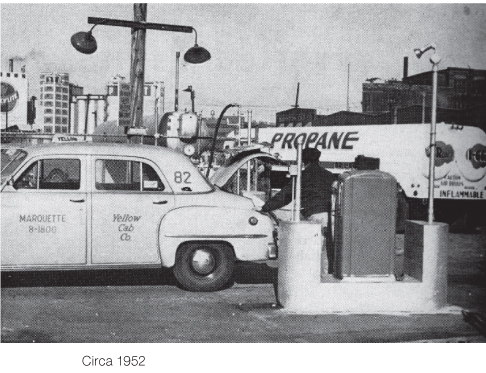

VEHICLE CONVERSIONS

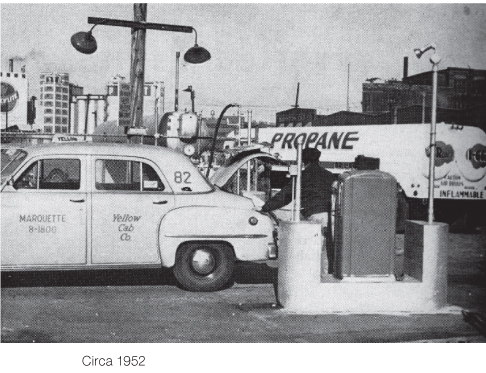

In about 1952, a man well versed in propane carburetion, Carl Abell, joined the staff. His initial assignment was to write the “Power Manual,” which proved an invaluable tool for marketers who were getting into the motor vehicle conversion business. This was at the time when gasoline-fueled vehicles, especially farm tractors, were low in power. By milling the heads to reduce the volume of the combustion chamber, mechanics could step up the compression ratio, increasing the engine’s power. But the low-octane gasolines of the era produced detonation, (knocking) so the engines were by necessity converted to burn higher-octane propane.

The fuel performed so efficiently that at least one manufacturer began supply factory-equipped propane buses. At one time the Chicago Transit Authority was operating 1700 of them. Until even more powerful diesels took over the bus and farm tractor markets, this method of providing extra power was rather widely used.

Carl Abell, incidentally, became editor of Butane-Propane News, remaining in that capacity until his death in 1958.

By 1953, most moms-and-pops had grown to the extent that pop no longer drove a delivery truck, so the old Reader’s Digest size didn’t seem to make sense any longer. Pop now had an office in which to do his reading. So Jenkins decided to enlarge the format to its present size.

During the time, the face of the industry was beginning to change. The trend toward consolidations in both the marketing and supplier segments was well under way. A number of regional marketing firms were already well established, and the push was on for them to become nationwide.

Two Western regionals, Petrolane and Suburban Gas out of Southern California, began what appeared to be a race to spread their wings across the country. Sacramento-based California Liquid Gas was not too far behind, at least for a time. Both Petrolane and Suburban Gas were among the first marketers to be listed on the New York Stock Exchange. These companies, of course, have long

since been swallowed up by other national firms.

At the same time, tank manufacturers, a major source of income for the magazine, were beginning to step on each other’s toes, and so one by one most of them sold out to Trinity Steel. With the wild growth of prior years slowing perceptibly, Jay Jenkins, ever the astute businessman, saw the handwriting on the wall and sold both magazines to the Chilton Co., a moderate-sized publishing firm headquartered in Philadelphia. The deal was consummated in early 1956, the year after advertising revenues had peaked for each magazine. Things were never to be the same again.

In 1958, following the death of Carl Abell, I was named editor.

But there were frustrations that mixed with the joys of the job. One was the failure of agricultural flaming to find a market. In the early 1960s, producers were plagued by overproduction, and large-volume storages had not as yet attained the volumetric capacity that they have today. In the summer, producers were often forced to sell their product at give-away prices just to get rid of it.

NEVER REALLY CAUGHT ON

So GPA and NPGA (then NLPGA) got together on a research and development program that they hoped would build new markets for the excess product. At the heart of it was a long-running series of seminars and cooperative programs with ag university professors to prove the viability of flaming as an alternative to pesticides.

But it never wholly caught on. Pesticides are easier to use, the chemical companies were underwriting a lot of the university’s research on their own products, and some farmers found the heat from the tractor-towed flamers a bit too uncomfortable. After all, when they could have air conditioned, radio equipped tractors with enclosed cabs, why put up with discomfort from any other source??

Then there was the carburetion market, which has never succeeded in becoming a profit center for marketers either. Too many problems. In the early 1950s, BPN launched a “Power Section” as a regular department, but the demise of the principal carburetion manufacturers—Century, Beam (a sellout), J&S, a company whose name escapes me (which sold out to American Bosch Arma, which ran it into the ground in a hurry), and others—reduced the advertising volume so sharply that it could no longer sustain the editorial effort.

During the 1960s there was a steady erosion in advertising, mostly because of these factors but partially because the Chilton Co. mounted only a feeble advertising space-selling effort. And also because of the mergers of both marketing companies and manufacturers, which reduced advertising lineage.

From almost the time it took over the magazine in 1956, Chilton Co. was unable to produce a winning P&L. For several years I kept studying the P&Ls, satisfying myself that I could make a go of it with even fewer ad pages by cutting out corporate overhead, eliminating certain staff positions, and dropping some unprofitable activities. It was a matter of the economics of small, lean and mean vs. overstuffed larger companies. But I was given no opportunity to prove my thesis.

Not, that is, until 1969, when a piece of bad news proved to be happy news for me. A “palace” revolt, in which I was only tangentially involved, ended up with the firing of the publisher and my being named publisher as well as editor. Subsequent office politics resulted in GAS being moved to Houston and the company deciding to discontinue BPN. I was not fired—my jobs were simply eliminated, and I was rewarded with a rather puny severance check.

After its demise was announced, a partner (whom I later bought out) and I decided to keep the magazine going. Even though some advertisers quit us because they didn’t think a broken-down editor could run a business, we survived—and thrived. Fortunately, it didn’t take much capital to keep it running long enough to finally reassure the skeptics.

A NIGHTMARE FOR PRODUCERS

The way has not always been easy, as witness the 1970s. It produced some setbacks for the industry and for the magazine, due in large part to a stupid decision by President Nixon to impose price controls on the economy to counter a modest inflationary trend. Ironically, his action and the ensuing actions by government bureaucrats eventually helped send inflation into orbit. Even though he saw the light enough to lift price controls on most products a year or two after he imposed them, he retained them on various petroleum products for most of the decade. In fact, it was not until Ronald Reagan assumed the presidency in 1981 that the controls were removed from propane.

The decade was a nightmare for producers and marketers alike due to the proliferation of government rules and the burgeoning of a vast bureaucracy, which evolved into today’s Energy Department. The end result of all this was the prolongation of a “crisis” in the petroleum business that was largely government induced. It was also a decade that was held hostage to a Middle East cartel that sent prices skyrocketing and brought about two brief gasoline shortages.

Among the stupid controls were allocations rules that tied sellers of petroleum products to buyers and buyers to sellers. In view of the situation, a number of producers cut their close marketing ties to marketers. Since government mandates forbade marketers from changing suppliers and suppliers from abandoning marketers, production no longer felt the need to cozy up to marketers, for the latter were a captive market. Accordingly, there was a period when every ring of the phone brought trepidation in our offices as we waited for the word that another producer was dropping his advertising. They figured they didn’t need us now.

All in all, though, the past 30 years have been the most rewarding for the magazine, as well as for its younger brother, The Weekly Propane Newsletter, founded in 1971, and The International Butane-Propane Newsletter. Even the 1970s were not without at least one major compensation. With the profusion of controls and the attendant confusion, marketers thirsted for information out of Washington, and it was our role to help bring it to them. In fact, the 1970s were so replete with governmentally-induced problems that a separate history could be written about them.

Things have since settled down, but new government-created traumas still exist. As of today, even though price and allocation controls are long gone, government still hangs like an albatross around the industry’s collective neck. In a most disheartening sort of way, though, it does keep everything interesting for a publication. However, we love the industry enough that we wish it weren’t so.

Nineteen-ninety-nine marks Butane-Propane News’ 60th year. Or is it really its 68th? Or, if you are one to literally believe the volume number published on this page, only its 31st?

Nineteen-ninety-nine marks Butane-Propane News’ 60th year. Or is it really its 68th? Or, if you are one to literally believe the volume number published on this page, only its 31st?All three ages have validity. BPN was actually born in 1931—68 years ago—as a section in a magazine, long defunct, called Western Gas. In fact, for many years after we became a separate magazine our motto was, “Headquarters for LP-Gas Information Since 1931.” The slogan was factually accurate for a number of years, but as the industry grew and matured, and as NPGA’s role expanded, we voluntarily relinquished our claim to the distinction. The association is now the true “headquarters.”

As for the volume number 31, that refers to the date when my wife and I took over ownership. Since the magazine had already been declared moribund by its previous owners, we decided to start afresh at Vol. 1.

Any way to calculate its age, BPN has been a part of the industry from the time propane marketing was beginning to emerge as a viable member of the family of fuels.

GOING BACK TO THE 1920s

BPN’s roots are traceable to the mid-twenties—it seems to me it was 1925; while that date might not be accurate, it’s close—when a native Oklahoman named Jay Jenkins moved to Southern California and launched Western Gas. In those days, when air travel was virtually non-existent and long-distance trucking was in its infancy, the Western states were little more than an enclave. The Rocky Mountains were a major barrier to the east-west commerce, so the Western markets were primarily provincial; thus regional

publications were a healthy and growing industry.

Western Gas was conceived as strictly a gas utility

Western Gas was conceived as strictly a gas utilitypublication, but it didn’t remain so forever.

As for the LPG business, it was largely centered in the mid-Eastern seaboard area, the product itself having first been stripped out of a mixture of hydrocarbons at a plant in Sistersville, W. Va. and having been introduced to the public as a residential fuel in 1912 in Pittsburgh. Growth was slow, even in the East. But in the 1920s two of the true pioneers in the business, the Kerr cousins, moved to Southern California and organized a business known as Rockgas. At about the same time, Western producers were also becoming interested in marketing the product.

And so was at least one gas utility, Southern Counties Gas Co., now a part of Southern California Gas Co. SoCounties saw the youngster as a means of entrée into markets beyond the reach of the gas mains, so about 1930 it began an active program of development. And Jay Jenkins, the astute business man, perceived the situation as an opportunity to expand his magazine’s readership and advertising potential. Thus was Butane-Propane News born as a section in Western Gas.

In those days, the product was generally delivered to market as a mixture, which was called “butane-propane.” Hence the rather clumsy name of the new section, which we and the former owners have chosen to perpetuate because of the magazine’s long-standing reputation, even though most of the marketed product is now predominantly propane.

As the decade of the’’30s wore on, transcontinental communications and travel became steadily more rapid, and the hump of the Rockies no longer posed a significant barrier to commerce. So, in 1937, Jay Jenkins decided to take Western Gas national, challenging the two New York-based magazines, the venerable American Gas Journal and the well-established Gas Age. He dropped the name “Western,” so the name became simply GAS. (Parenthetically, none of the three magazines is still in existence.)

Then, in 1939, he decided to sever BPN’s umbilical cord, making it a magazine in its own right. His timing, which under ordinary situations would have been excellent, proved a bit premature, as the entry of the U.S. into World War II two and a half years later stunted the growth of both magazines until Japan surrendered in 1945.

Paper was short, ink was probably short, everything that manufacturers produced was diverted to the war effort. Many consumer products were discontinued, prices were strictly controlled, and advertising suffered. Yet with government regulations proliferating (sound familiar?), it gave BPN an opportunity to play an important role in publishing and interpreting the often onerous and frequently confusing rules.

Postwar, the magazine proved a perfect fit for a rapidly growing industry. It was the age of moms-and-pops, with thousands of brand new entrepreneurs springing up every year. Many borrowed a few bucks, bought a truck, found a producer who would give them a helping hand, and began peddling cylinders around the countryside. Many others went into the bulk delivery business with money loaned by the banks or by a relative or two.

Most of them needed education in handling the product. So BPN expanded its role as “Headquarters for LP-gas Information.” It was published in the old Reader’s Digest size, which fit neatly into a truck’s glove compartment. And it became in effect a traveling library for the owner/driver. The size proved very popular among the young entrepreneurs. It featured a “Letters” department, which printed and answered myriad technical questions, most of which were rather elementary, since most of the growing corps of marketers were neither chemists nor engineers. Over the years this department was handled by two “technical editors,” both very capable industry engineers. Some old-timers might still remember Lester Luxon, who fulfilled the role after the first man died. At the time, Luxon was chief engineer for Algas, which was then located in Southern California.

The company also published the “Handbook Butane-Propane Gases,” which proved very popular and went into several printings and updates during its life span. Again, this strengthened the magazine’s reputation as headquarters for

LP-gas information.

The late 1940s and the early 1950s were halcyon years for both GAS and Butane-Propane News. Both industries were roaring ahead with rapid growth—in the case of LPG, its growth reportedly matched that of the electronics industry. Advertising revenues zoomed. The tank business, in particular, was soaring. It seemed as if every street corner in Texas had sprouted a tank manufacturer.

Business was so good that Jay Jenkins, riding high, decreed that any company that did not buy two-page spreads would not find its ad in the front of the magazines (which at that time was a preferred position). Companies’ annual budgets of 24 full pages were not uncommon. In 1955, their peak year, both GAS and Butane-Propane News ran more than 1200 pages of advertising—100 pages per month—and the folio of many issues totaled 200 pages, ads and editorial combined, or more.

VEHICLE CONVERSIONS

In about 1952, a man well versed in propane carburetion, Carl Abell, joined the staff. His initial assignment was to write the “Power Manual,” which proved an invaluable tool for marketers who were getting into the motor vehicle conversion business. This was at the time when gasoline-fueled vehicles, especially farm tractors, were low in power. By milling the heads to reduce the volume of the combustion chamber, mechanics could step up the compression ratio, increasing the engine’s power. But the low-octane gasolines of the era produced detonation, (knocking) so the engines were by necessity converted to burn higher-octane propane.

The fuel performed so efficiently that at least one manufacturer began supply factory-equipped propane buses. At one time the Chicago Transit Authority was operating 1700 of them. Until even more powerful diesels took over the bus and farm tractor markets, this method of providing extra power was rather widely used.

Carl Abell, incidentally, became editor of Butane-Propane News, remaining in that capacity until his death in 1958.

By 1953, most moms-and-pops had grown to the extent that pop no longer drove a delivery truck, so the old Reader’s Digest size didn’t seem to make sense any longer. Pop now had an office in which to do his reading. So Jenkins decided to enlarge the format to its present size.

During the time, the face of the industry was beginning to change. The trend toward consolidations in both the marketing and supplier segments was well under way. A number of regional marketing firms were already well established, and the push was on for them to become nationwide.

Two Western regionals, Petrolane and Suburban Gas out of Southern California, began what appeared to be a race to spread their wings across the country. Sacramento-based California Liquid Gas was not too far behind, at least for a time. Both Petrolane and Suburban Gas were among the first marketers to be listed on the New York Stock Exchange. These companies, of course, have long

since been swallowed up by other national firms.

At the same time, tank manufacturers, a major source of income for the magazine, were beginning to step on each other’s toes, and so one by one most of them sold out to Trinity Steel. With the wild growth of prior years slowing perceptibly, Jay Jenkins, ever the astute businessman, saw the handwriting on the wall and sold both magazines to the Chilton Co., a moderate-sized publishing firm headquartered in Philadelphia. The deal was consummated in early 1956, the year after advertising revenues had peaked for each magazine. Things were never to be the same again.

In 1958, following the death of Carl Abell, I was named editor.

But there were frustrations that mixed with the joys of the job. One was the failure of agricultural flaming to find a market. In the early 1960s, producers were plagued by overproduction, and large-volume storages had not as yet attained the volumetric capacity that they have today. In the summer, producers were often forced to sell their product at give-away prices just to get rid of it.

NEVER REALLY CAUGHT ON

So GPA and NPGA (then NLPGA) got together on a research and development program that they hoped would build new markets for the excess product. At the heart of it was a long-running series of seminars and cooperative programs with ag university professors to prove the viability of flaming as an alternative to pesticides.

But it never wholly caught on. Pesticides are easier to use, the chemical companies were underwriting a lot of the university’s research on their own products, and some farmers found the heat from the tractor-towed flamers a bit too uncomfortable. After all, when they could have air conditioned, radio equipped tractors with enclosed cabs, why put up with discomfort from any other source??

Then there was the carburetion market, which has never succeeded in becoming a profit center for marketers either. Too many problems. In the early 1950s, BPN launched a “Power Section” as a regular department, but the demise of the principal carburetion manufacturers—Century, Beam (a sellout), J&S, a company whose name escapes me (which sold out to American Bosch Arma, which ran it into the ground in a hurry), and others—reduced the advertising volume so sharply that it could no longer sustain the editorial effort.

During the 1960s there was a steady erosion in advertising, mostly because of these factors but partially because the Chilton Co. mounted only a feeble advertising space-selling effort. And also because of the mergers of both marketing companies and manufacturers, which reduced advertising lineage.

From almost the time it took over the magazine in 1956, Chilton Co. was unable to produce a winning P&L. For several years I kept studying the P&Ls, satisfying myself that I could make a go of it with even fewer ad pages by cutting out corporate overhead, eliminating certain staff positions, and dropping some unprofitable activities. It was a matter of the economics of small, lean and mean vs. overstuffed larger companies. But I was given no opportunity to prove my thesis.

Not, that is, until 1969, when a piece of bad news proved to be happy news for me. A “palace” revolt, in which I was only tangentially involved, ended up with the firing of the publisher and my being named publisher as well as editor. Subsequent office politics resulted in GAS being moved to Houston and the company deciding to discontinue BPN. I was not fired—my jobs were simply eliminated, and I was rewarded with a rather puny severance check.

After its demise was announced, a partner (whom I later bought out) and I decided to keep the magazine going. Even though some advertisers quit us because they didn’t think a broken-down editor could run a business, we survived—and thrived. Fortunately, it didn’t take much capital to keep it running long enough to finally reassure the skeptics.

A NIGHTMARE FOR PRODUCERS

The way has not always been easy, as witness the 1970s. It produced some setbacks for the industry and for the magazine, due in large part to a stupid decision by President Nixon to impose price controls on the economy to counter a modest inflationary trend. Ironically, his action and the ensuing actions by government bureaucrats eventually helped send inflation into orbit. Even though he saw the light enough to lift price controls on most products a year or two after he imposed them, he retained them on various petroleum products for most of the decade. In fact, it was not until Ronald Reagan assumed the presidency in 1981 that the controls were removed from propane.

The decade was a nightmare for producers and marketers alike due to the proliferation of government rules and the burgeoning of a vast bureaucracy, which evolved into today’s Energy Department. The end result of all this was the prolongation of a “crisis” in the petroleum business that was largely government induced. It was also a decade that was held hostage to a Middle East cartel that sent prices skyrocketing and brought about two brief gasoline shortages.

Among the stupid controls were allocations rules that tied sellers of petroleum products to buyers and buyers to sellers. In view of the situation, a number of producers cut their close marketing ties to marketers. Since government mandates forbade marketers from changing suppliers and suppliers from abandoning marketers, production no longer felt the need to cozy up to marketers, for the latter were a captive market. Accordingly, there was a period when every ring of the phone brought trepidation in our offices as we waited for the word that another producer was dropping his advertising. They figured they didn’t need us now.

All in all, though, the past 30 years have been the most rewarding for the magazine, as well as for its younger brother, The Weekly Propane Newsletter, founded in 1971, and The International Butane-Propane Newsletter. Even the 1970s were not without at least one major compensation. With the profusion of controls and the attendant confusion, marketers thirsted for information out of Washington, and it was our role to help bring it to them. In fact, the 1970s were so replete with governmentally-induced problems that a separate history could be written about them.

Things have since settled down, but new government-created traumas still exist. As of today, even though price and allocation controls are long gone, government still hangs like an albatross around the industry’s collective neck. In a most disheartening sort of way, though, it does keep everything interesting for a publication. However, we love the industry enough that we wish it weren’t so.