It’s OK — everybody does it: Amid a seemingly endless series of announcements of propane company acquisitions in recent years, almost every business owner has thought to themselves, “I wonder what my company is worth?” Those who are already considering selling might take the next step by getting a business valuation in preparation for a sale. Owners who plan on continued near-term operation, on the other hand, may simply resign themselves to the unknown, quietly speculating about multiples and prices with each new headline. But what many owners may not know is that obtaining a valuation for their business can be beneficial even well before the prospects of retirement or sale enter the picture.

Small and midsize businesses might already be familiar with some common situations in which business valuations can be useful — companies owned by multiple family members may get a valuation to ensure fairness when one owner buys out another. Some will also have encountered a need for business valuation to aid in securing new financing from a bank or investor. One lesser-known role for business valuation, however, arises from another popular business planning practice: the conversion from a C corporation to an S corporation.

By now, many owners will have heard — in these pages or from their own advisors — that structuring their business as an S corporation has the potential to eliminate “double taxation” of business earnings and to significantly lower their total tax burden. For most owners, this will mean a lower effective tax rate on earnings and more money in their pocket at the end of the year. An S corporation often also has the added benefit of lowering an owner’s tax burden when the time comes to sell a business. However, the conversion from a C corporation to an S corporation comes with some important caveats that can punish owners if they’re not well-prepared. Proper planning, including a business valuation, can be key to protecting the value of your company and savings on taxes in this process.

The key wrinkle in an S corporation conversion is the built-in gains (BIG) tax, which can be assessed on newly converted S corporations if they take in significant income from the sale of certain assets during the five-year recognition period mandated by the IRS post-conversion. This BIG tax on income from the sale of an appreciated asset is assessed at the prior C corporation corporate income tax rate, and it’s payable in addition to the tax paid by an owner on their share of the net gain when it’s realized as personal income. In other words, you’re back to double taxation! No wonder your accountant will tell you over and over to wait five years from your conversion to sell anything.

For most new S corporations, this won’t be an issue — they’ll be content to wait out the five-year recognition period to lock in the lower tax rates on any sale. In other cases, however, an owner who didn’t obtain a business valuation at the time of their conversion could find themselves facing a big tax bill. And because unforeseen circumstances like health issues or financial difficulties could force the sale of assets, or even the whole business prior to the end of the recognition period, it’s better to be prepared. A business valuation will put a stake in the ground as of your conversion date, assigning clear values to each of your business assets to ensure that any taxable gains are understood and that you can keep a lid on your total tax owed.

Consider the example of a propane business owner, Mr. Jones, who has operated his business as a C corporation for 15 years. After consulting with his accountant, Mr. Jones decides to convert to an S corporation in order to reduce the share of his income lost to taxes. He also chooses to get a business valuation, which values his business assets on the date of conversion — including real estate, trucks, propane tanks and business goodwill — at a total of $5 million, an increase of $3 million over their tax basis values.

Now suppose that Mr. Jones falls ill and is unable to continue running the business, necessitating that he and his family sell the company in year four post-conversion. The business sells for $10 million, but because the transaction closed before the end of the five-year recognition period, the owner’s take-home figure will be subject to built-in gains tax. Specifically, he’ll be paying BIG taxes — federal corporate income taxes plus tax on his distributions as a shareholder — on the $3 million of gains over tax basis that was determined through his valuation on the conversion date. Painful, yes, but also clear and defensible to the IRS.

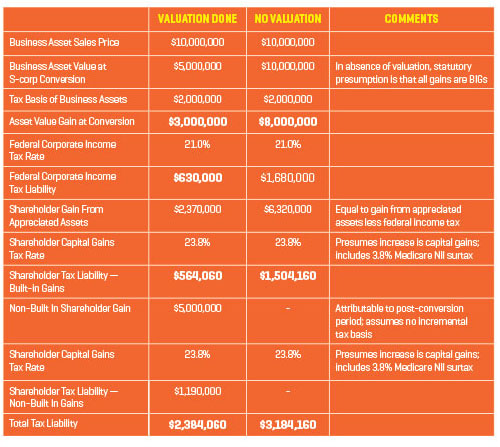

Let’s take a look at a simplified estimate of the tax burden on the Jones family’s sale in this situation, as well as under an alternative scenario where no valuation had been performed at the time of S corporation conversion. For the sake of simplicity, this analysis ignores certain other potential taxes, such as any state taxes, that could be payable in conjunction with a sale.

In Figure 1, the built-in gains tax is applied to the increase in value of the assets that was established as of the S corporation conversion date. Appreciation that occurs post-conversion or from new assets is not subject to the BIG double tax. Mr. Jones, planning ahead, obtained a valuation that identified his unrealized built-in gains as $3 million at the time of conversion and limited his BIG tax burden. By contrast, in an alternative scenario where he failed to obtain a valuation, his total tax liability could be increased by more than $800,000!

Why the difference? The simple answer is that without the defensible figures provided by a reliable third-party valuation, Mr. Jones could be on the hook for the BIG double tax on the whole purchase price. The IRS regulations related to built-in gains assume that all gains recognized by an S corporation during the recognition period are taxable built-in gains unless the taxpayer can prove otherwise — something many propane business owners may not be in a position to do. Attempting to establish acquisition dates and values for assets over time while under the scrutiny of an IRS audit is no easy task, particularly when an owner may not have ready access to business records post-sale. But by obtaining a valuation ahead of time, Mr. Jones was able to cut his tax bill in our example by more than a third.

Closing the sale of a business should be a positive event for an owner, with the prospects of more free time to spend with family and personal interests, not to mention the sale proceeds to serve as a nice nest egg.

The last thing anybody wants to run into is the potential for a giant tax bill or an IRS audit. So, when you’re looking ahead and considering an S corporation transition, keep a couple of things in mind.

First, your accountant is right — try to wait out the five-year recognition period before selling if at all possible to make sure you minimize your tax liability. But no less critical to a good outcome is to do your future self a favor and get a business valuation when you convert. At the end of the day, it’s a small price to pay with the potential for exponential savings. And it might just help to satisfy that business-value curiosity of yours at the same time.