Wednesday, January 13, 2016

By Richard Fredenburg . . .

Our meter calibrators get complaints from propane dealers every summer about “losing” gas. Since nearly all dealers have temperature compensators (TCs) on their delivery meters, it seems to be a universal concern. However, there doesn’t seem to be a concern in the winter when the “losses” are reversed. Let’s look at the way temperature compensation works so you can understand what is happening.

A TC is a device that monitors the temperature of propane going through the metering device. Its purpose is to deliver a constant heating value of fuel to a customer no matter its temperature. Since propane is less dense at higher temperatures, there is less heating value to a gallon of propane in the summer than there is in a gallon of propane in the winter. The TC makes an adjustment to the meter so the customer gets the same heat energy (the same number of Btus) in a metered (billed) gallon, no matter when the fuel is delivered.

This is a complicated issue to cover in a written article, but I’ll try to explain what is happening.

Consider a gallon bucket. Say that I put one gallon of a liquid at 60ºF in that container, so it is completely full with nothing overflowing. If we cool that gallon by 20° to 30°, we can see the container isn’t full anymore. Similarly, if we heat it to 80° to 90°, it will overflow. This example will work with water, but the effect is more pronounced with propane…except that a bucket doesn’t work as well with propane.

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Handbook 44 carries the imposing title of “Specifications, Tolerances, and Other Technical Requirements for Weighing and Measuring Devices.” (That’s why we just call it NIST Handbook 44.) It has a requirement that LP-gases shall be dispensed from temperature-compensated meters. Most states adopt Handbook 44, so this article should be pertinent to nearly all locations.

We are going to crunch some numbers here. If you don’t want to get into the numbers with me, skip down to the JUMP TO HERE about five paragraphs down. Stay with me and we will get into some complicated, fun, and, for some, confusing, number talk.

LP-gas meter compensation is normalized to 60°F. A compensated meter and an uncompensated meter will deliver identical gallons at 60°F, assuming everything is working properly. If the temperature gets to 80°, the uncompensated meter will still deliver a gallon, but it will have fewer Btus of energy. A compensated meter delivers something else (volumetrically), but it will have the same number of Btus as when it was 60°.

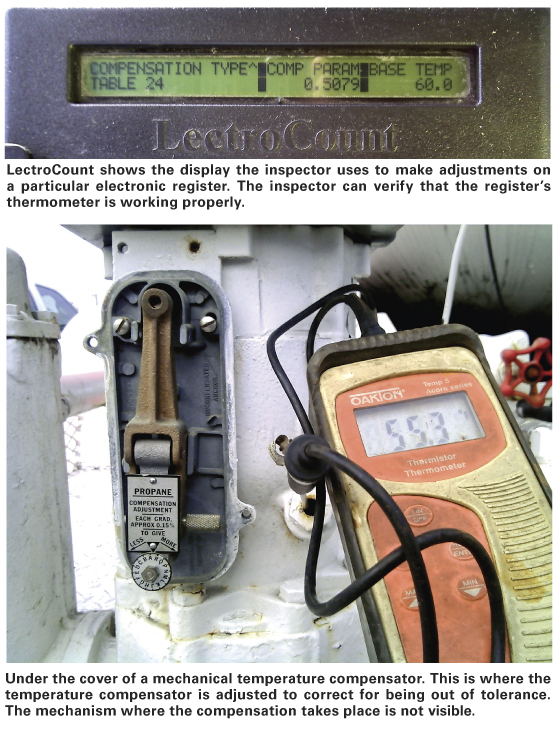

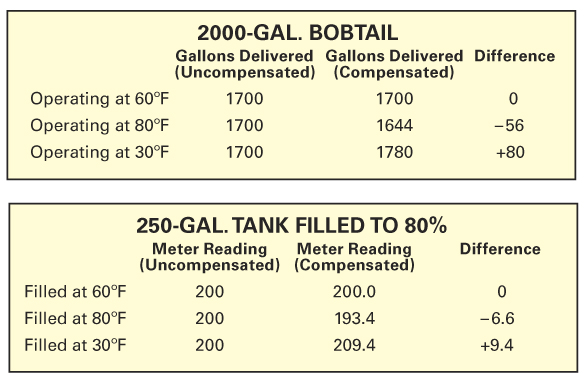

Now consider a 250-gal. propane tank that does an impossible thing; it neither expands when heated nor shrinks when cooled. (If we have to consider the tank’s volume change with temperature, I’ll get lost!) The tank is normally filled to 80%. If you start with an empty tank, you will put 200 gallons into it. If the propane is 60° when you fill it, your meter should read 200. If it is 80°, you still fill it to the same 80% level and there will be 200 actual gallons in it and that’s what an uncompensated meter will read. However, the compensated meter will read something less than 200. It will be more like 193.4, a difference of nearly 7 gallons. Similarly, if it is 30°, the tank will still be filled to the 200-gallon level (80%) if you read a gauge on the tank or fill by the bleed valve, but the compensated meter will read that 209.4 gallons were delivered. That’s a swing of 16 gallons over 50°.

Stay with me, we’re almost done. This is where you find out where your gas is “going.”

At 80º, the compensated meter delivers 1.034 gallons for each gallon showing on the register, including the totalizer. When the temperature drops to 30º, the compensated meter delivers 0.955 gallons for each gallon showing on the register. To illustrate what this means, consider this: A 2000-gal. bobtail filled to 85% at the bulk plant will have 1700 gallons of its container space filled with propane. (Disregard losses due to using fuel from the tank to run the motor, and assume the tank can be completely emptied.) The driver goes to make his deliveries. However, when the driver returns after unloading the whole tank, the meter will show only 1644 gallons (1700 divided by 1.034) were delivered on the summer route, a “loss” of 56 gallons. In the winter, that same 1700 gallons will show as 1780 metered gallons (1700 divided by 0.955), a “gain” of 80 gallons. That’s a swing of 136 gallons from the same bobtail. Of course, these numbers change if the average temperatures are other than 80° and 30°.

That’s how the numbers work. Believe me on this. This article is not the place to try to explain how to do the numbers. However, if you want to explore for yourself, look at the LP-Gas Code, Annex F, Liquid Volume Tables, Computations, and Graphs. The numbers I calculated came from using Table F.3.3, Liquid Volume Correction Factors.

JUMP TO HERE. Welcome back.

So, if everything is adjusted for temperature, why does it seem gas is being lost? Easy. Not everything is really being adjusted for temperature. NIST Handbook 44 requires TC only for delivery to consumers.

First, let’s discuss what is adjusted. Propane coming from most pipelines and terminals is metered through temperature-compensated meters. Propane coming from many rail terminals is “compensated” because the terminal determines the amount of the load by weighing it. A gallon-equivalent of propane weighs the same amount, whether it is a light, “large” gallon at a higher temperature or a dense, “small” gallon at a lower temperature. Note that a truckload will be lighter in the summer and heavier in the winter if it is filled to the same level both times. Weighing the load is a true measure of fuel delivery.

What is not compensated? The gauge on tanks, be they rotogauges, magnetic level gauges, or any other gauge based only on volume. And that’s on all tanks; bulk plants, bobtails, transports, railcars, and residential tanks. Meters delivering out of bulk plants? Who knows? You need to find out. Since the bobtails may be filled according to uncompensated meters and/or gauges and make deliveries through compensated meters, there will be a discrepancy anytime they deliver product that is not 60°. Since I don’t know how railcars are filled, all we can read is the fill level, an uncompensated determination. However, you may be billed for a compensated amount if they are filled through a compensated meter. (Maybe it will have a thermometer so you can get its temperature at that part of the car. The pressure will also be a good indicator of its temperature, but that is a topic for another article.)

Want one more complication? Commercial propane doesn’t always have the same density at a given temperature. But that’s enough about that for now, except to say that it has to do with the impurities. (A former boss thinks that would make a good Ph.D. dissertation.)

You will have to determine which parts of your operation are compensated and which aren’t, and how that affects your inventory. If you typically come up short on inventory in the summer and are over on inventory in the winter (Yeah, right!), consider the effects of your temperature-compensated meters.

The bottom line? If you deliver through temperature-compensated meters, expect to appear to come up short in the summer and over in the winter.

Remember, this is not an attempt to get you to take the compensators off, this is an explanation of what may be happening to your inventory. There’s also that NIST Handbook 44 requirement for using temperature compensation.

Richard Fredenburg is LP-gas engineer for the North Carolina Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Standards Division. Most of its issues deal with safety, but there is also a weights and measures aspect to its work.

Our meter calibrators get complaints from propane dealers every summer about “losing” gas. Since nearly all dealers have temperature compensators (TCs) on their delivery meters, it seems to be a universal concern. However, there doesn’t seem to be a concern in the winter when the “losses” are reversed. Let’s look at the way temperature compensation works so you can understand what is happening.

A TC is a device that monitors the temperature of propane going through the metering device. Its purpose is to deliver a constant heating value of fuel to a customer no matter its temperature. Since propane is less dense at higher temperatures, there is less heating value to a gallon of propane in the summer than there is in a gallon of propane in the winter. The TC makes an adjustment to the meter so the customer gets the same heat energy (the same number of Btus) in a metered (billed) gallon, no matter when the fuel is delivered.

This is a complicated issue to cover in a written article, but I’ll try to explain what is happening.

Consider a gallon bucket. Say that I put one gallon of a liquid at 60ºF in that container, so it is completely full with nothing overflowing. If we cool that gallon by 20° to 30°, we can see the container isn’t full anymore. Similarly, if we heat it to 80° to 90°, it will overflow. This example will work with water, but the effect is more pronounced with propane…except that a bucket doesn’t work as well with propane.

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Handbook 44 carries the imposing title of “Specifications, Tolerances, and Other Technical Requirements for Weighing and Measuring Devices.” (That’s why we just call it NIST Handbook 44.) It has a requirement that LP-gases shall be dispensed from temperature-compensated meters. Most states adopt Handbook 44, so this article should be pertinent to nearly all locations.

We are going to crunch some numbers here. If you don’t want to get into the numbers with me, skip down to the JUMP TO HERE about five paragraphs down. Stay with me and we will get into some complicated, fun, and, for some, confusing, number talk.

LP-gas meter compensation is normalized to 60°F. A compensated meter and an uncompensated meter will deliver identical gallons at 60°F, assuming everything is working properly. If the temperature gets to 80°, the uncompensated meter will still deliver a gallon, but it will have fewer Btus of energy. A compensated meter delivers something else (volumetrically), but it will have the same number of Btus as when it was 60°.

Now consider a 250-gal. propane tank that does an impossible thing; it neither expands when heated nor shrinks when cooled. (If we have to consider the tank’s volume change with temperature, I’ll get lost!) The tank is normally filled to 80%. If you start with an empty tank, you will put 200 gallons into it. If the propane is 60° when you fill it, your meter should read 200. If it is 80°, you still fill it to the same 80% level and there will be 200 actual gallons in it and that’s what an uncompensated meter will read. However, the compensated meter will read something less than 200. It will be more like 193.4, a difference of nearly 7 gallons. Similarly, if it is 30°, the tank will still be filled to the 200-gallon level (80%) if you read a gauge on the tank or fill by the bleed valve, but the compensated meter will read that 209.4 gallons were delivered. That’s a swing of 16 gallons over 50°.

Stay with me, we’re almost done. This is where you find out where your gas is “going.”

At 80º, the compensated meter delivers 1.034 gallons for each gallon showing on the register, including the totalizer. When the temperature drops to 30º, the compensated meter delivers 0.955 gallons for each gallon showing on the register. To illustrate what this means, consider this: A 2000-gal. bobtail filled to 85% at the bulk plant will have 1700 gallons of its container space filled with propane. (Disregard losses due to using fuel from the tank to run the motor, and assume the tank can be completely emptied.) The driver goes to make his deliveries. However, when the driver returns after unloading the whole tank, the meter will show only 1644 gallons (1700 divided by 1.034) were delivered on the summer route, a “loss” of 56 gallons. In the winter, that same 1700 gallons will show as 1780 metered gallons (1700 divided by 0.955), a “gain” of 80 gallons. That’s a swing of 136 gallons from the same bobtail. Of course, these numbers change if the average temperatures are other than 80° and 30°.

That’s how the numbers work. Believe me on this. This article is not the place to try to explain how to do the numbers. However, if you want to explore for yourself, look at the LP-Gas Code, Annex F, Liquid Volume Tables, Computations, and Graphs. The numbers I calculated came from using Table F.3.3, Liquid Volume Correction Factors.

JUMP TO HERE. Welcome back.

So, if everything is adjusted for temperature, why does it seem gas is being lost? Easy. Not everything is really being adjusted for temperature. NIST Handbook 44 requires TC only for delivery to consumers.

First, let’s discuss what is adjusted. Propane coming from most pipelines and terminals is metered through temperature-compensated meters. Propane coming from many rail terminals is “compensated” because the terminal determines the amount of the load by weighing it. A gallon-equivalent of propane weighs the same amount, whether it is a light, “large” gallon at a higher temperature or a dense, “small” gallon at a lower temperature. Note that a truckload will be lighter in the summer and heavier in the winter if it is filled to the same level both times. Weighing the load is a true measure of fuel delivery.

What is not compensated? The gauge on tanks, be they rotogauges, magnetic level gauges, or any other gauge based only on volume. And that’s on all tanks; bulk plants, bobtails, transports, railcars, and residential tanks. Meters delivering out of bulk plants? Who knows? You need to find out. Since the bobtails may be filled according to uncompensated meters and/or gauges and make deliveries through compensated meters, there will be a discrepancy anytime they deliver product that is not 60°. Since I don’t know how railcars are filled, all we can read is the fill level, an uncompensated determination. However, you may be billed for a compensated amount if they are filled through a compensated meter. (Maybe it will have a thermometer so you can get its temperature at that part of the car. The pressure will also be a good indicator of its temperature, but that is a topic for another article.)

Want one more complication? Commercial propane doesn’t always have the same density at a given temperature. But that’s enough about that for now, except to say that it has to do with the impurities. (A former boss thinks that would make a good Ph.D. dissertation.)

You will have to determine which parts of your operation are compensated and which aren’t, and how that affects your inventory. If you typically come up short on inventory in the summer and are over on inventory in the winter (Yeah, right!), consider the effects of your temperature-compensated meters.

The bottom line? If you deliver through temperature-compensated meters, expect to appear to come up short in the summer and over in the winter.

Remember, this is not an attempt to get you to take the compensators off, this is an explanation of what may be happening to your inventory. There’s also that NIST Handbook 44 requirement for using temperature compensation.

Richard Fredenburg is LP-gas engineer for the North Carolina Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Standards Division. Most of its issues deal with safety, but there is also a weights and measures aspect to its work.