Wednesday, February 15, 2017

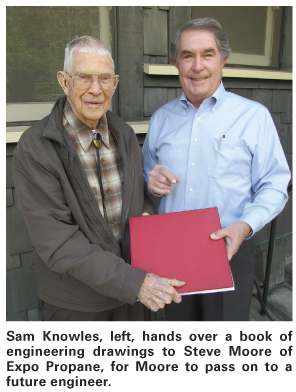

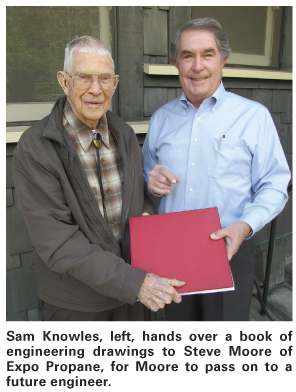

The number on Sam Knowles’ engineering license is 8077, which his friend Steve Moore of Expo Propane (Bellflower, Calif.) believes is one of the oldest civil engineering licenses issued in California. Knowles, who will turn 96 in April, built tank structures for many propane companies in California throughout his career before retiring his license last year.

“When I went to a city to get a permit, once in a while the permit person at the counter who reviews the plans would say, ‘Wow, this is one of the oldest numbers I’ve ever seen,’ which is a real tribute,” said Moore, whose company is part of Energy Distribution Partners (EDP; Chicago). Knowles performed engineering work for Expo Propane, and prior to that in the 1970s for Moore’s previous company, Mutual Propane. “A lot of people support our industry, and you could call them unsung heroes. They don’t often get recognized for the job they do.”

Moore wanted to recognize Knowles, who has performed all of the necessary structural engineering for propane tank foundations at Moore’s companies since he started out in the propane industry in 1978. He explained how he first crossed paths with Knowles, noting that commercial installations of horizontal propane tanks did not need a concrete foundation in the early days.

“Because of the Los Angeles topography where there’s never enough space, we had customers who wanted a vertical propane tank installation,” Moore said. “Therefore, we always required structural engineering and a concrete foundation for that. That’s how we connected with Sam.”

Knowles estimates that he has designed hundreds of tank structural foundations for propane companies in California and other states. But it all started when he developed an interest in engineering while in high school. His stepfather was a residential and commercial builder.

“I liked the idea of building things,” Knowles recalled. “I was good at mathematics, and it was just logical that I felt this would be an area of great interest.” He went on to earn a civil engineering degree from Stanford University, and Standard Oil of California recruited him immediately after his Stanford graduation. He supervised the building of pipelines that moved crude oil to refineries and then transported finished products such as gasoline and kerosene to distribution centers. He also worked at Douglas Aircraft in California, where his engineering department built the C-54 Skymaster transport that the U.S. Army Air Force employed in World War II. Knowles later returned to Stanford and obtained a graduate degree in engineering. He met his wife, Ginny, now 92, while at Stanford. He earned his civil engineering license in 1951.

“Then the Navy called me to serve during World War II,” he recounts. “I spent half my time in the Navy learning to be a flying aircraft radio technician.” He also spent time in Guam after the war to replace personnel who had been discharged.

He worked for Mobil Oil, Union Oil, and Tosco before launching his own structural engineering services business. His first exposure to propane came when his business worked with the marketing department at Union Oil in California, which ran propane distribution centers. “Propane [marketers] who furnished the tanks realized that our firm could be of use to them in providing the engineering that was required to build the tanks and install them,” Knowles said. His firm provided engineering plans for propane marketers’ propane plants, and also helped propane companies assist their commercial customers with plans for installing propane tanks for fueling forklifts and autogas vehicles.

Knowles ran his company with a partner for 20 years before continuing in the business on his own for another 35 years. He also served for 14 years on the planning commission for the city of South Pasadena, Calif. and for 12 years on the South Pasadena City Council. He was mayor of South Pasadena for three different years in the 1980s.

His engineering license was still active until he officially retired last year. As the years went on, the longevity of his engineering license became a novelty. “I had an experience in San Marino [Calif.], where the planning director didn’t believe I really existed,” Knowles said. “I had to go over and show him I was alive and I had a number.” He added that the stamp showing the engineering license number is called a wet stamp, which is imprinted on structural engineering plans. The personnel at the city or other entity validates the stamp, which certifies the drawing as legal. “Building departments want a wet stamp rather than a copy,” Knowles said, adding that he still has his wet stamp.

One of Knowles’ sons, also an engineer, gently persuaded him to retire his engineering license last year, and Knowles’ license now hangs in his son’s San Francisco office. Knowles’ other son is a chiropractor.

Moore said his nonagenarian friend and colleague “has been an important support person for our company. Our good working experience has turned into a friendship.”

—Daryl Lubinsky

“When I went to a city to get a permit, once in a while the permit person at the counter who reviews the plans would say, ‘Wow, this is one of the oldest numbers I’ve ever seen,’ which is a real tribute,” said Moore, whose company is part of Energy Distribution Partners (EDP; Chicago). Knowles performed engineering work for Expo Propane, and prior to that in the 1970s for Moore’s previous company, Mutual Propane. “A lot of people support our industry, and you could call them unsung heroes. They don’t often get recognized for the job they do.”

Moore wanted to recognize Knowles, who has performed all of the necessary structural engineering for propane tank foundations at Moore’s companies since he started out in the propane industry in 1978. He explained how he first crossed paths with Knowles, noting that commercial installations of horizontal propane tanks did not need a concrete foundation in the early days.

“Because of the Los Angeles topography where there’s never enough space, we had customers who wanted a vertical propane tank installation,” Moore said. “Therefore, we always required structural engineering and a concrete foundation for that. That’s how we connected with Sam.”

Knowles estimates that he has designed hundreds of tank structural foundations for propane companies in California and other states. But it all started when he developed an interest in engineering while in high school. His stepfather was a residential and commercial builder.

“I liked the idea of building things,” Knowles recalled. “I was good at mathematics, and it was just logical that I felt this would be an area of great interest.” He went on to earn a civil engineering degree from Stanford University, and Standard Oil of California recruited him immediately after his Stanford graduation. He supervised the building of pipelines that moved crude oil to refineries and then transported finished products such as gasoline and kerosene to distribution centers. He also worked at Douglas Aircraft in California, where his engineering department built the C-54 Skymaster transport that the U.S. Army Air Force employed in World War II. Knowles later returned to Stanford and obtained a graduate degree in engineering. He met his wife, Ginny, now 92, while at Stanford. He earned his civil engineering license in 1951.

“Then the Navy called me to serve during World War II,” he recounts. “I spent half my time in the Navy learning to be a flying aircraft radio technician.” He also spent time in Guam after the war to replace personnel who had been discharged.

He worked for Mobil Oil, Union Oil, and Tosco before launching his own structural engineering services business. His first exposure to propane came when his business worked with the marketing department at Union Oil in California, which ran propane distribution centers. “Propane [marketers] who furnished the tanks realized that our firm could be of use to them in providing the engineering that was required to build the tanks and install them,” Knowles said. His firm provided engineering plans for propane marketers’ propane plants, and also helped propane companies assist their commercial customers with plans for installing propane tanks for fueling forklifts and autogas vehicles.

Knowles ran his company with a partner for 20 years before continuing in the business on his own for another 35 years. He also served for 14 years on the planning commission for the city of South Pasadena, Calif. and for 12 years on the South Pasadena City Council. He was mayor of South Pasadena for three different years in the 1980s.

His engineering license was still active until he officially retired last year. As the years went on, the longevity of his engineering license became a novelty. “I had an experience in San Marino [Calif.], where the planning director didn’t believe I really existed,” Knowles said. “I had to go over and show him I was alive and I had a number.” He added that the stamp showing the engineering license number is called a wet stamp, which is imprinted on structural engineering plans. The personnel at the city or other entity validates the stamp, which certifies the drawing as legal. “Building departments want a wet stamp rather than a copy,” Knowles said, adding that he still has his wet stamp.

One of Knowles’ sons, also an engineer, gently persuaded him to retire his engineering license last year, and Knowles’ license now hangs in his son’s San Francisco office. Knowles’ other son is a chiropractor.

Moore said his nonagenarian friend and colleague “has been an important support person for our company. Our good working experience has turned into a friendship.”

—Daryl Lubinsky