Thursday, July 9, 2015

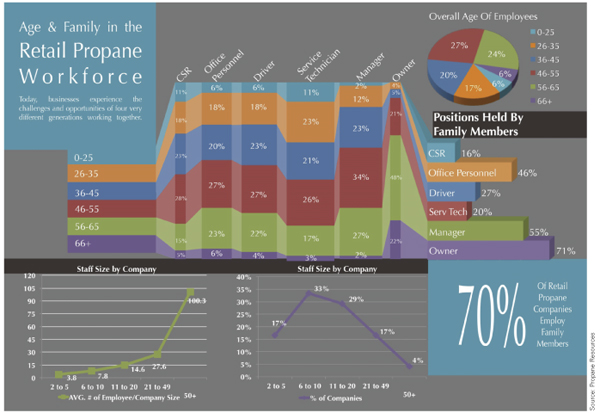

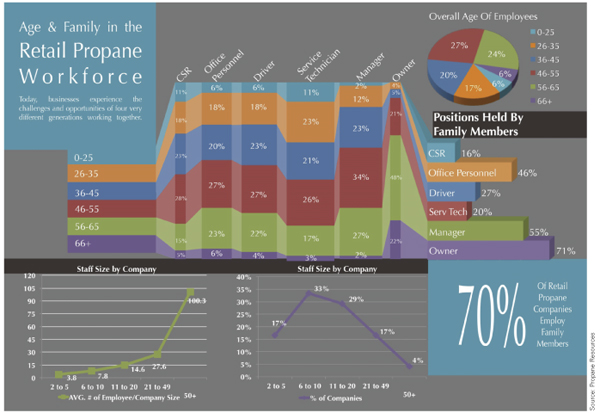

Most propane businesses, excluding the majors, are family businesses. With four generations involved with the operations, communications and the ability to work together can be challenging. The four generations are: the traditionalists, the baby boomers, the Generation X-ers, and Generation Y-ers or millennials. Soon a fifth, the Generation Z-ers, will be joining the workforce. Getting all these different generations to work together as a cohesive team is one challenge facing business owners, but how to transition the ownership of the business is a greater concern. And what is the “right” answer — sell to a third party, or pass the company to the next generation? Owners are facing both questions.  Tamera Kovacs of Propane Resources spoke about the changing family dynamic of propane businesses in a presentation titled, “The Generation Gap — Who’s Running Your Business?” at the National Propane Gas Association Southeastern Conference in April and at the Western Propane Trade Show & Convention in May. She focused on understanding the generational dynamics and ownership transition.

Tamera Kovacs of Propane Resources spoke about the changing family dynamic of propane businesses in a presentation titled, “The Generation Gap — Who’s Running Your Business?” at the National Propane Gas Association Southeastern Conference in April and at the Western Propane Trade Show & Convention in May. She focused on understanding the generational dynamics and ownership transition.

Kovacs believes understanding the generational differences is critical to increasing communications and work productivity, not to mention communications between the different generations. Gain an understanding of what influenced each generation; what they value; and what their views are on workplace ethic, authority, and communication. Couple this knowledge with how each generation views dealing with money and their ideas on technology, and many of the daily challenges you have been facing may become easier to understand. It is important to understand how each group is motivated and how the groups prefer to interact. Understand what they bring to the workforce by way of strengths and liabilities, and learn the keys to working with each group. The more you understand the differences of each generation, the higher the probability of facilitating a work atmosphere that capitalizes on each generation’s strengths and increasing communications.

“Every generation has something to learn from someone else,” Kovacs said in an interview with BPN before the conferences. “And I think being able to work together and understand one another and pull the benefits from each generation to build a strong company is what’s really key.”

She has seen a major shift in how the different generations believe businesses should be operated and what they want to get out of the business. Owners in the age 50 to 80 range are thinking about retirement and safety nets and want to make sure their retirement funds are secure. However, the Generation-X-ers and Generation-Y-ers want to grow the business, change it, and make it more relevant.

That family dynamic means communication is necessary about each generation’s responsibilities in the business. The younger generation might be taking on more responsibility, but the previous generation might not give the younger generation the authority to make decisions. The younger family members might have the responsibility of running the operations of the business but might not have purchasing authority. Kovacs believes responsibility and authority are two very different things.

“You might have the responsibility to make sure deliveries are made, but do you have the authority to make investments in technology to improve the efficiencies?” she asked.

Communication is crucial, and the different generations must understand that each age group uses different methods of communication. The younger generation might recommend that the business increase efficiencies by using smart phones in the service department, especially if the company has a lot of new service technicians. The use of facetime to show a fellow service technician a problem with an installation may save a second senior service technician the drive time if there is a simple solution. The younger generation may also want to market the business by using information gathered and the latest technology. They may want to use the latest social media outlets to reach different members of the company’s customer base — targeted marketing. The previous generation, however, might say, “Why are we wasting time on websites and social media? We’ve been using the Yellow Pages all these years; it’s worked.”

“Each generation’s techniques may be effective, but does that younger generation have the authority to make those changes in the business?” Kovacs asked. “It is important to understand what drives each generation, each one’s communication style, and the keys to working with each generation.”

She discussed how no two family dynamics are the same. Some of them are willing to let the younger generations make changes and get their feet wet and make mistakes. Others are so hands-on and in control that they’re not willing to give that authority to someone else.

The 50- to 80-year-olds are deciding whether to sell their business or pass their legacy down to the next generation. Some will decide to sell because the next generation shows little interest in the company. Others wonder if their family members who are involved with the business have put enough work into it. Kovacs has seen several propane company owners who don’t allow their children to do anything but make deliveries, so that younger generation does not have the skills necessary to run the business because they have never had decision-making authority. She has seen other companies in which the younger generation is mostly running the company and the older generation is mainly an overseer.

So what should families do? “That is the $64,000 question, and that is also something [for which] no two families are going to have the same answer,” Kovacs said. Deciding who the right person is to take over the business is a key issue, but deciding the timing of the transition is most critical. Harvard Business School professor John A. Davis, in “Enduring Advantage, Collected Essays on Family Enterprise,” writes, “You need to make a leadership transition not when the outgoing leader is ready to leave, but when the incoming successor is ready to lead.”

Ownership and leadership should not be considered one and the same, contends Kovacs. Just because an individual has ownership in the company does not mean he or she has the skills to lead the company, yet another complication with family business but one that should not be overlooked. “Normally, you would say the oldest son will take the lead in the business,” Kovacs noted. “But is he necessarily the one that should be doing it? The point is, who is the right person, because it may not necessarily be the one next in line. You’ve got to look at their strengths and look at what they can bring in terms of leadership and goals for the company. Just because he’s the oldest son doesn’t mean he’s the one to lead the business.”

Kovacs has recently seen several companies in which the younger generations are coming back into the family business, and the older generations are beginning to shift the responsibilities and authority.

“If you think about it, there are more family businesses in this industry than not,” she noted. “And no two are handling the passing of ownership or dealing with responsibilities and authority the same way. When it comes to transferring ownership and leadership, it is critical to have a transition plan, and that transitional period may take several years to implement.”

Every generation has its strong and weak points and has something to learn from the other generations.

“I think being able to work together, understand one another, and pull the good from each generation to build a strong company is what’s really key.”

She talked about a hypothetical situation in which an 80-year-old and a 25-year-old are partners in a sack race. The traditionalist might plan to simply work together to get to the finish line. But the millennial might say, “Why don’t we cut the bottom out of the sack and run? They didn’t tell us we couldn’t do that.” They have the same end goal in mind, but the traditionalists, the boomers, the Generation X-ers and the millennials will all do things differently.

“But you can agree on the end goal and the general concept of how to get there, understanding that your minds are going to work differently,” she stated. “Maybe the new way is not bad, it’s just different, and it’s new and scary. But it’s good to at least have the discussion of what the possibilities are.”

Three-Generation Rule:

• Of 100 family-owned business, 30 will make it to the second generation.

• Of 100 family-owned companies, only 14 will make it to the third generation.

Source: John A. Davis, “Enduring Advantage, Collected Essays on Family Enterprise.”

Kovacs believes understanding the generational differences is critical to increasing communications and work productivity, not to mention communications between the different generations. Gain an understanding of what influenced each generation; what they value; and what their views are on workplace ethic, authority, and communication. Couple this knowledge with how each generation views dealing with money and their ideas on technology, and many of the daily challenges you have been facing may become easier to understand. It is important to understand how each group is motivated and how the groups prefer to interact. Understand what they bring to the workforce by way of strengths and liabilities, and learn the keys to working with each group. The more you understand the differences of each generation, the higher the probability of facilitating a work atmosphere that capitalizes on each generation’s strengths and increasing communications.

“Every generation has something to learn from someone else,” Kovacs said in an interview with BPN before the conferences. “And I think being able to work together and understand one another and pull the benefits from each generation to build a strong company is what’s really key.”

She has seen a major shift in how the different generations believe businesses should be operated and what they want to get out of the business. Owners in the age 50 to 80 range are thinking about retirement and safety nets and want to make sure their retirement funds are secure. However, the Generation-X-ers and Generation-Y-ers want to grow the business, change it, and make it more relevant.

That family dynamic means communication is necessary about each generation’s responsibilities in the business. The younger generation might be taking on more responsibility, but the previous generation might not give the younger generation the authority to make decisions. The younger family members might have the responsibility of running the operations of the business but might not have purchasing authority. Kovacs believes responsibility and authority are two very different things.

“You might have the responsibility to make sure deliveries are made, but do you have the authority to make investments in technology to improve the efficiencies?” she asked.

Communication is crucial, and the different generations must understand that each age group uses different methods of communication. The younger generation might recommend that the business increase efficiencies by using smart phones in the service department, especially if the company has a lot of new service technicians. The use of facetime to show a fellow service technician a problem with an installation may save a second senior service technician the drive time if there is a simple solution. The younger generation may also want to market the business by using information gathered and the latest technology. They may want to use the latest social media outlets to reach different members of the company’s customer base — targeted marketing. The previous generation, however, might say, “Why are we wasting time on websites and social media? We’ve been using the Yellow Pages all these years; it’s worked.”

“Each generation’s techniques may be effective, but does that younger generation have the authority to make those changes in the business?” Kovacs asked. “It is important to understand what drives each generation, each one’s communication style, and the keys to working with each generation.”

She discussed how no two family dynamics are the same. Some of them are willing to let the younger generations make changes and get their feet wet and make mistakes. Others are so hands-on and in control that they’re not willing to give that authority to someone else.

The 50- to 80-year-olds are deciding whether to sell their business or pass their legacy down to the next generation. Some will decide to sell because the next generation shows little interest in the company. Others wonder if their family members who are involved with the business have put enough work into it. Kovacs has seen several propane company owners who don’t allow their children to do anything but make deliveries, so that younger generation does not have the skills necessary to run the business because they have never had decision-making authority. She has seen other companies in which the younger generation is mostly running the company and the older generation is mainly an overseer.

So what should families do? “That is the $64,000 question, and that is also something [for which] no two families are going to have the same answer,” Kovacs said. Deciding who the right person is to take over the business is a key issue, but deciding the timing of the transition is most critical. Harvard Business School professor John A. Davis, in “Enduring Advantage, Collected Essays on Family Enterprise,” writes, “You need to make a leadership transition not when the outgoing leader is ready to leave, but when the incoming successor is ready to lead.”

Ownership and leadership should not be considered one and the same, contends Kovacs. Just because an individual has ownership in the company does not mean he or she has the skills to lead the company, yet another complication with family business but one that should not be overlooked. “Normally, you would say the oldest son will take the lead in the business,” Kovacs noted. “But is he necessarily the one that should be doing it? The point is, who is the right person, because it may not necessarily be the one next in line. You’ve got to look at their strengths and look at what they can bring in terms of leadership and goals for the company. Just because he’s the oldest son doesn’t mean he’s the one to lead the business.”

Kovacs has recently seen several companies in which the younger generations are coming back into the family business, and the older generations are beginning to shift the responsibilities and authority.

“If you think about it, there are more family businesses in this industry than not,” she noted. “And no two are handling the passing of ownership or dealing with responsibilities and authority the same way. When it comes to transferring ownership and leadership, it is critical to have a transition plan, and that transitional period may take several years to implement.”

Every generation has its strong and weak points and has something to learn from the other generations.

“I think being able to work together, understand one another, and pull the good from each generation to build a strong company is what’s really key.”

She talked about a hypothetical situation in which an 80-year-old and a 25-year-old are partners in a sack race. The traditionalist might plan to simply work together to get to the finish line. But the millennial might say, “Why don’t we cut the bottom out of the sack and run? They didn’t tell us we couldn’t do that.” They have the same end goal in mind, but the traditionalists, the boomers, the Generation X-ers and the millennials will all do things differently.

“But you can agree on the end goal and the general concept of how to get there, understanding that your minds are going to work differently,” she stated. “Maybe the new way is not bad, it’s just different, and it’s new and scary. But it’s good to at least have the discussion of what the possibilities are.”

Three-Generation Rule:

• Of 100 family-owned business, 30 will make it to the second generation.

• Of 100 family-owned companies, only 14 will make it to the third generation.

Source: John A. Davis, “Enduring Advantage, Collected Essays on Family Enterprise.”